Can entrepreneurship solve the youth unemployment crisis?

March 05, 2014

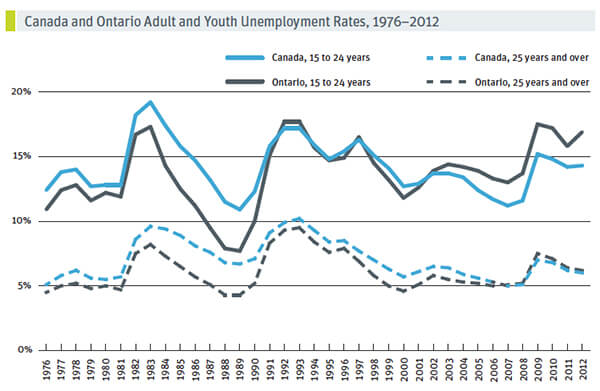

Since the start of the 2008 global financial crisis, young workers in Ontario have taken a pounding. As “The Young and the Jobless,” my report on youth employment in Ontario, shows, the gap between the employment rates of those workers over the age of 25 and young workers ages 15 to 24 is not only greater than we have seen in our province’s history, but it is also higher than in any other Canadian province. Moreover, the jobs that have been created for young people are increasingly casual. In 1997, one-quarter of the jobs held by young workers in Ontario were temporary; today that number is over one-third.

While there are opportunities to improve youth employment through supporting youth entrepreneurship, mishandling self-employment promotion could make matters for young workers far worse than they already are.

High-turnover economy with few incentives for youth

What we are really seeing here is a young generation living in a new economic climate, one that is replacing the older employment model their parents grew up with. This old employment model is the one we usually think of as the norm for the mid-20th century in Canada. Large employers, like the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in my old Etobicoke neighbourhood of Lakeshore, employed thousands of workers, most of whom bargained collectively for their employment contracts through unions like the United Steelworkers. These long-term contracts provided job security and good working conditions for workers, while employers benefited from a low turnover workforce who they could invest in developing, leading to higher wages for workers and higher profits for employers.

Unlike their parents and grandparents, today’s young workers are living in a high-turnover economy with few incentives for employers to invest in their development. Instead, companies are pushing the costs and risks involved in training onto young workers themselves. These young workers are being asked to take on a greater burden of paying for post-secondary education that will produce ready-to-work employees. However, there are skills that must be learned on the job and many companies are not providing young workers with the opportunities to learn them.

Self-employment: Two distinct flavours

Self-employment can seem like a way of sidestepping this trap, but for many it makes instability and low productivity even worse. Broadly, we can think of entrepreneurship as coming in two distinct flavours: inspiration and desperation. The entrepreneurs of inspiration are those who have the ideas, skills and investment to be able to create viable businesses. The entrepreneurs of desperation are those who are often on the margins of our economy, just scraping by. They would usually rather have a regular job and self-employment seems to be their only access to work, albeit work without adequate income security and workplace protection. We need to reduce the negative consequences for young entrepreneurs and incentivise skill development and workplace protection. Discussion is being had. The Ideas Forum: Ontario Youth Jobs Strategy explored these alarming statistics and trends in January, bringing Canada’s leading thinkers, entrepreneurs, youth workers, policy-makers, small business advisors and employment experts to MaRS to discuss ways to help stimulate youth employment.

But part of the responsibility here lies with government. Current income support programs are poorly designed for meeting the needs of people with unstable incomes. The institution of a guaranteed annual income would go a long way to supporting self-employed people who are living near or in poverty. Furthermore, public investment in the physical and social infrastructure that reduces the personal cost of creating a startup—such as affordable childcare and broader health coverage—would help those who are looking to create a new business.

Modernize old practices and revitalize others

We also need to rediscover and modernize old practices that we can use to support each other. The large company and large union bargaining models of the mid-20th century were not the first successful models of workplace collective action. An earlier generation of late 19th- and early 20th-century young workers faced highly fluid labour markets with few individual protections—much like what we see emerging today—and developed their own organizations to reduce the risks these markets generated. Craft unions, credit unions, friendly societies and a variety of producer and consumer cooperatives all provided mutual insurance against market excesses and a firm foundation that people could use to invest in each other.

We need to bring many of these old mutual support practices back and we also need to invent new ones. We should look to revitalize the credit union sector to invest in local social enterprises across this province, and we should develop new craft unions to support freelancers working in the new professions we see emerging every day, such as 3D printing and social media. We also need to look to new net-enabled mutual support models, such as crowdfunding and collaborative consumption, to bring new energy to our collective efforts.

If we build new mutual support mechanisms we can create job opportunities and convert desperation entrepreneurs into inspiration entrepreneurs. If we don’t, then we’re taking young people who are already on the edge and putting them one dry spell, one bad contract or one workplace injury away from being pushed over.