The Evolving Digital Utility: The convergence of energy and IT

August 12, 2014

This is the third report in the Connected World Market Insights Series.

IT for a smarter grid, smarter home and a smarter customer

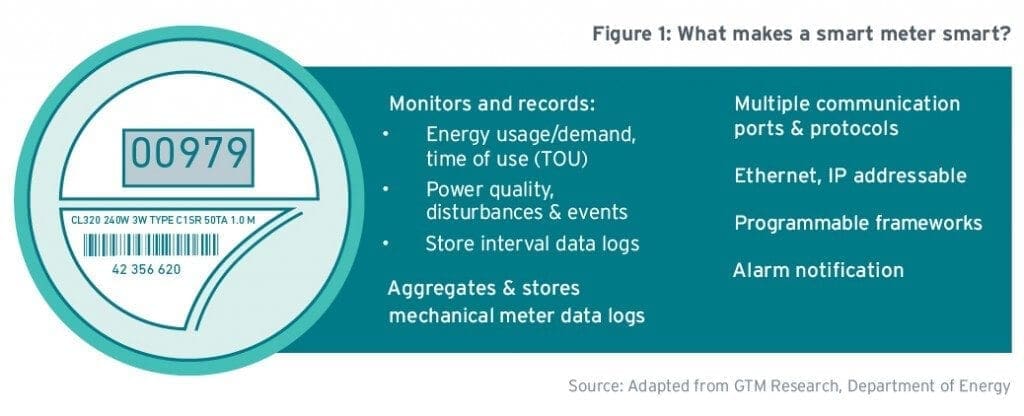

Information technology (IT) makes the smart grid possible. It is also a major driver of energy efficiency. As utilities work toward building smart grids with IT, they are turning to smart meters and advanced metering infrastructure as a key first step in adding intelligence to energy networks. The smart meter brings utilities into the home, where battle lines are being drawn as traditional home-based IT players (such as telecom and security companies) already have a foothold in this market.

Advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) is the two-way communication between a smart meter and the utility,1 and includes meter data management (MDM), smart meters and associated communication infrastructure. Utilities traditionally have an antiquated system that is incapable of supporting an overlay of communications technology—such as broadband over power line (BPL) and wireless technologies—which limits the utility’s ability to optimize reliability, maximize and optimize asset utilization, enable energy markets, increase grid security and reduce electricity prices.2 With AMI, utilities are taking strides to overcoming this challenge. AMI is just a subset of the bigger picture, but it is the portion closest to the customer.

Advanced metering infrastructure systems enable customer engagement activities via this two-way communication capability between the home and the utility. This evolution in the utility’s relationship with customers is entirely new and will revolutionize energy-efficiency gains in households and businesses.

The advanced metering infrastructure market by the numbers

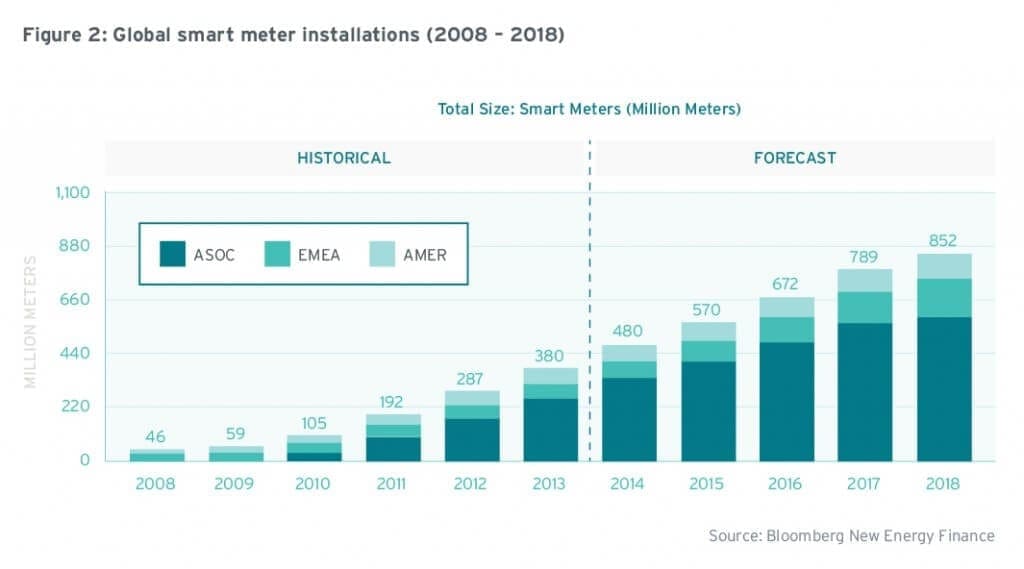

Frost & Sullivan, a market research firm,3 puts the revenue cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) of the AMI market at 15.8% during the forecast period 2012–2017. Frost estimates this CAGR to be lower in North America, at 5.6% (2012–2017). AMI market growth is driven by smart meters, which capture 41% of the AMI market revenues.4 Frost & Sullivan estimates that sales for MDM, combined with customer and program data management, are expected to account for 32.6% of total AMI sales by 2016, compared to just 30.0% in 2011.5 Navigant Research6 forecasts that there will be 131 million smart meter shipments globally in 2018, declining to 114 million shipments per year by 2022 as meters reach high penetration levels. In the graph below, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) forecasts a total of 852 million meter installations globally by 2018, reflecting the growth pointed out by Navigant.

The smart meter market is growing in the United States, stabilizing in Ontario

In North America, the United States has more than 3000 utilities with over 146 million customers. In 2012, 533 American electric utilities had more than 43 million AMI installations. This represents only about 30% of the addressable AMI market, which comprises 146 million end points. In Canada, the smart meter market is led by British Columbia and Ontario. Hydro Quebec is joining these leaders as it rolls out a 3.75 million meter project. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]Ontario has rolled out smart meters for 4.8 million commercial and residential customers[/inlinetweet].

Green Button was brought forward by the Ontario’s Ministry of Energy and facilitated by MaRS. The first step was Download My Data, a secure data transfer directly from the utility to the customer in a consistent format. The Green Button standard was released in spring 2013; it allows energy usage information to be shared in a common format (XML), 24 hours after usage occurs, complete with privacy measures. So far, the data standard only applies to electricity—but it can be expanded to gas and water data too, and it is relevant for residential, commercial and industrial market segments.The Connect My Data (CMD) pilot, an automated, secure electronic data transfer from the utility to a third party, based on customer authorization, is currently underway. The CMD pilots have been implemented in London Hydro and Hydro One’s service territories and will run for 12 months.The main objectives of the pilots are: to test the implementation of the Green Button standard; to undertake a comprehensive process review; and to document the findings to help other utilities and solutions providers learn about best practices and lessons to consider when implementing the standard across Ontario. In the US, where the standard was first adopted, 35 utilities have implemented Green Button, and 44 have committed. These 35 utilities represent 36 million homes and businesses. |

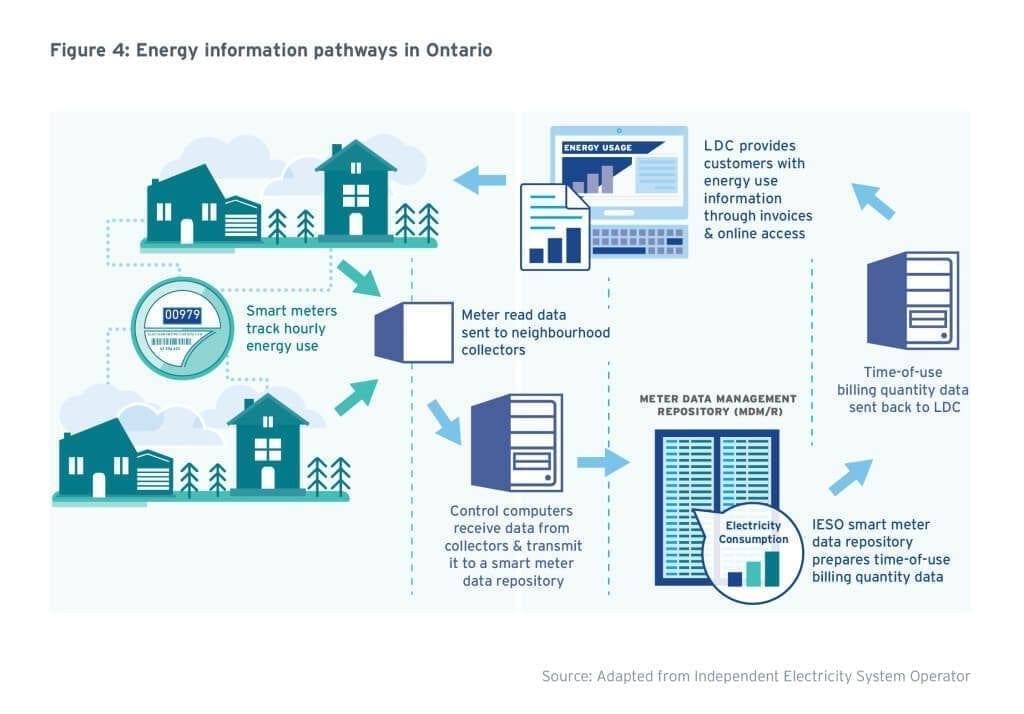

Ontario’s meter data management repository (MDM/R) processes the data from these smart meters and fulfills 200 to 300 thousand billing determinant requests every day. Currently this data is used by utilities for time-of-use (TOU) pricing and billing, and additional valuable uses for this data are opening up due to initiatives such as the Green Button Program. There is now a large amount of data available, and we could be doing a lot more with it. According to BNEF, the greatest value from smart meter data will continue to come from applications that include outage management, distribution automation, asset management, customer engagement and load forecasting.

Data deluge

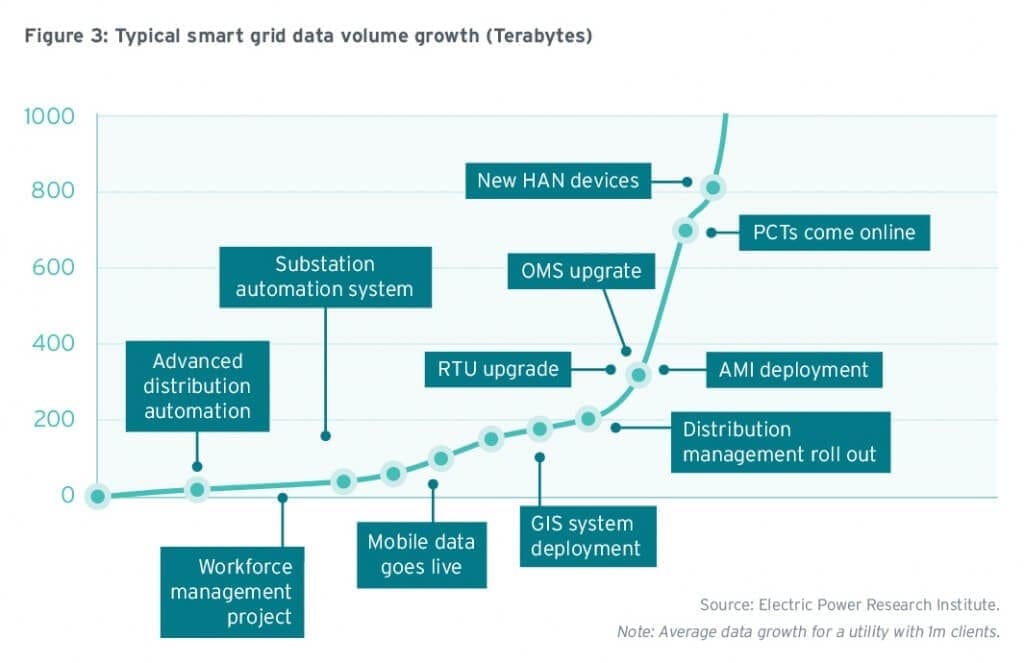

A smart meter that is reporting data at 15-minute intervals will generate 400MB of data a year; extrapolating from that, a utility implementing AMI to a million customers will generate 400TB of data a year. In 2012, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]BNEF predicted 680 million smart meter installations globally by 2017—leading to 280PB of data a year[/inlinetweet]. This is not the only data utilities are dealing with, by far. The BNEF graph below demonstrates the exponential increase in the quantities of smart grid data for a vertically integrated utility with about a million customers.7

Meter data management

This brings us back to an innovative IT component—meter data management (MDM). The MDM manages the data collected from AMI; it is the data repository and what makes interval data from a plethora of meters accessible for TOU pricing, load forecasting, outage management and operational processes. It is the platform that metering service companies use to provide useful access to supply-and-demand data. Meter data management processes and isolates the right data for a billing or analytical application.8 MDM is a flexible and scalable AMI solution. It is the key to driving benefits in AMI because it will integrate new technologies for storing, managing and assimilating new data into existing systems.

In Ontario, smart meters track hourly energy use. This data is sent to neighbourhood collectors, from which it is sent to control computers, then transmitted to a centralized, independent electricity system operator (IESO)-controlled MDM/R. Time-of-use billing quality data is then sent to the local distribution companies (LDCs), also known as utilities, for readers outside Ontario. The LDCs then provide customers with energy use information through a web portal and paper invoices. (See Figure 4, below.) Throughout this process, the consumers’ data is completely secure, as privacy has been baked into Ontario’s smart meter data management system.

Turning data into insights: data analytics

Frost and BNEF already see a trend in MDM vendors offering analytics services to utilities in order to provide those utilities with add-on capabilities for data processing, as well as providing analysis that adds value beyond the data upload. This is allowing utilities to exploit the smart grid infrastructure they have deployed to date. By using data analytics, utilities can predict load and demand, help consumers determine where they can find the best cost-savings through increased energy efficiency, and help large facilities to optimize their building operations, among many other applications.

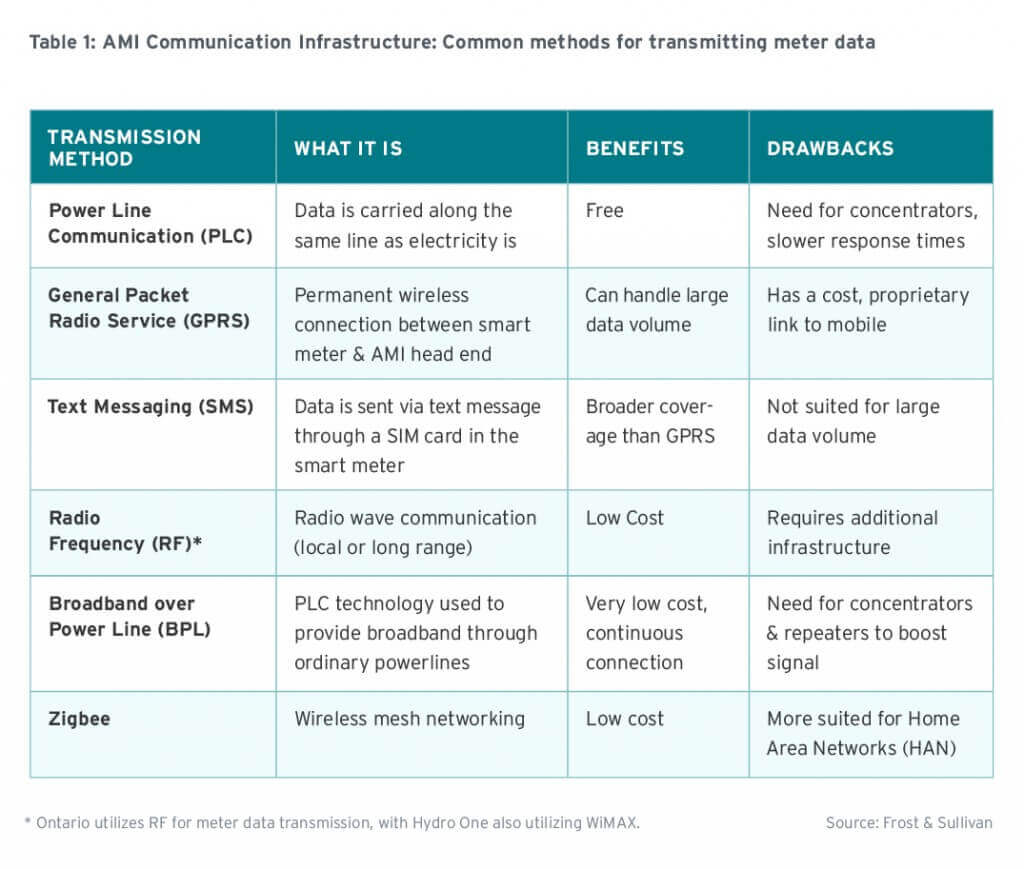

Moving information

Information from smart meters is automatically and wirelessly sent over a secure network to the utility. Data is first sent to a neighbourhood area network (NAN) or wide area network (WAN) data concentrator. From there, it is relayed to the utility back office (utility head end).9 Figure 4 (above) shows the AMI structure in Ontario; table 1 (below) shows common methods for transmitting meter data along with some of the pros and cons associated with each method.

In Europe, power-line communication (PLC) is widely used for sending data from smart meters to data concentrators—according to BNEF, the two main types of network used for AMI are PLC and radio frequency (RF; also called private wireless). Power-line communication dominates, with 50% market share globally. Meanwhile, RF dominates in North America. Other promising technologies are general packet radio service (GPRS) Mesh, Zigbee, worldwide interoperability for microwave access (WiMAX), digital subscriber line (DSL) and fibre optic.10 Ontario’s Hydro One uses WiMAX and RF.

The home area network (HAN), or hubs, enables the sharing of meter data with various devices in the home. We go more into detail on HAN in “A Game of Homes: Communication, cooperation and entertainment in the connected world”, and in the next paper in this series: “Connected World: Home energy management”(title subject to change).

Market dynamics

Advanced metering infrastructure is key in supporting energy efficiency programs such as TOU pricing, through:

- Enabling load control and peak shifting through energy management,

- Facilitating consumer engagement (to varying degrees—depending on data intervals)

- Enabling power-sector decarbonization (for jurisdictions with carbon-intensive electricity production or carbon-heavy peaking plants)

- Enabling demand response

Advanced metering infrastructure allows utilities to communicate, for example, dynamic pricing, demand-response actions and outages back to consumers.

Government funding has been a key driver of AMI investments. In the US, there was significant AMI spending with the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). When that funding expired, a similar slowdown in the marketplace followed. With government funding for energy efficiency programs in decline, utilities are forced to rate-base these expenses, which can increase costs for energy consumers or lead to a reduction in AMI deployments (for example, by deferring or tightening the scope of the deployment). Gartner sees this trend as a barrier to AMI and MDM technologies becoming core smart grid technologies and enabling the utility of the future. Lack of foresight and investment could lead to a hodgepodge of stepwise improvements to the existing utility process, without any meaningful convergence of IT and energy delivery.

A made-in-Ontario solution

Smart grid development began early in Ontario, with an ambitious strategy for the deployment of smart meters in 2004.11 Ontario’s Smart Metering Initiative (SMI) aims to reduce the need for new generation sources, increase conservation, improve reliability, and provide more accurate and timely energy use information to customers.12 In their working paper, “Beyond Smart Meters,” Winfield and Wieler note the drivers for smart meters from 2004–2008 were to enable the province to move to TOU electricity pricing. This was done in order to shift to a demand-response (DR) strategy, which the province thought was required to better manage summer peaks in demand, as well as to deal with an aging asset base and anticipated further increases in demand.

Ontario’s MDM/R was procured and implemented in support of the Ministry of Energy’s specifications, established in 2006. The independent electricity system operator (IESO) was designated as the smart metering entity (SME) and managed the smart metering system implementation program (SMSIP) to procure, develop, implement and operate the MDM/R. The SMI is the overall Government of Ontario initiative to create a conservation culture and a toolset for demand management in Ontario.13 14

Policy as a market driver

Since 2009, the main market driver has been the Green Energy Act (GEA). In particular, the GEA sets a framework for smart grid development in Ontario, with several objectives, such as to expand opportunities for demand response, price information and load control15 to electricity customers, in order to provide customer control and consequently encourage energy conservation via smart meters, TOU rates, in-home displays and load control. Ontario’s Long Term Energy Plan continues this trend, and lays out some plans for conservation in the province, including an aim to reduce consumption by 30 terawatt hours by 2032, an aim to use demand response to meet 10% of peak demand by 2025, and continue with some key initiatives/programs, such as: SaveOnEnergy, Social Benchmarking pilot, Green Button Initiative, and the Smart Grid Fund.

Table 2: Advanced Metering Infrastructure Drivers |

| Lower operating expenses, such as labour for meter reading, improved reliability and operations, and online customer connection/disconnection |

| Increased efficiency—that is, minimizing the need for peak power generation and enhancing peak load management. This management can in turn reduce utility operating costs and increase revenues through better asset utilization. In jurisdictions with carbon-intensive electricity assets, AMI can be a driver for power generation decarbonization. |

| Enabling demand-response programs that help lower consumption during peak times, to avoid brownouts and blackouts. |

| Government policy— In Ontario, the government mandated that all utilities roll out smart meters by 2010, in order to facilitate greater energy efficiency literacy and awareness, enable the integration of smart home features, enable conservation programs and improve outage management. In the US, ARRA spending was a major driver. |

| Optimizing onsite renewable power generation and charging operations for plug-in electric vehicles, and reducing transmission network losses. |

| Electricity theft reduction (a partial driver in Canada, but in developing countries theft becomes a stronger driver) |

| Greater accuracy in billing |

Table 3: Advanced Metering Infrastructure Challenges |

| Data management issues: Increased data volume—the storage of rapidly increasing amounts of data and the ability to analyze this data in order to forecast. High volumes of data can quickly become unmanageable, making analysis and useful conclusions difficult. |

| Lack of interoperability standards: Interoperability refers to the variety of technologies and solutions that are able to work together, communicate and function together, despite being from different vendors and/or technology manufacturers. At present, technologies are not interconnected. Open standards are key in avoiding getting locked into anything proprietary. |

| Information and cyber security privacy concerns: Cyber security will constantly change as threats evolve, and security standards will also need to evolve. Because smart meters, communication infrastructure and MDM use Internet technology, they are vulnerable to cyber attacks. Meter providers and communications companies can mitigate this vulnerability by implementing data protection and security protocols. Ontario has made inroads in addressing these issues, in particular with the Green Button standard. One way of reducing customer pushback is to garner customer trust. To do so, it is critical that utilities and companies operating in this sector mitigate privacy concerns. |

| New technology risk/future-proof technology: Technology in this field is changing quickly, and the fear of technological obsolescence is real for utilities. Advanced metering infrastructure technologies also often do not have mass-scale proven business cases to demonstrate the benefits of implementing AMI. Technology implemented today needs to be easy to upgrade and integrate with technology of the future—future-proofing MDM components will go a long way toward alleviating fear of technology obsolesce, making sinking capital into MDM less of a risk.16 |

Scaling Ontario’s meter data management to real-time

Ontario and the US were ahead of many other jurisdictions in driving smart meter investment. In Ontario, reducing peak demand to avoid system pressures, avoid building new generation, and billing accuracy and shifting to TOU pricing were key motivations in rolling out smart meters. In other jurisdictions, utilities built their entire business case on the avoided cost of manual meter data collection, greater accuracy of billing and shifting to TOU pricing. In the US, ARRA led to high shipments of meters between 2009 and 2012. Some of these early meters were not fully functioning smart meters, as they only offered one-way meter reading (such as some in Ontario). Consequently, these meters are becoming dated already, with an expected lifetime of just 7 to 10 years, versus 15 to 20 years for fully functional smart meters.17 In Ontario, another key challenge has been that the MDM/R was installed before a set of common communication standards for AMI had been developed.18

Better data-mining capabilities, storage and retention are needed. Utilities should take care when planning and selecting communications and MDM technologies, in order to maximize the overall benefits of their AMI installations. As for the vendors, because installation of hardware does not generate a constant stream of revenue, higher margins can be gained in providing the software and network.19

With AMI and smart meters in particular, customers are provided with a platform to empower them to change their consumption patterns, first through TOU pricing, then through access to their data using programs like the Ontario Green Button Program, and later (and deeper) through access to real-time consumption data. Data gathered from smart meters is essential in order to implement demand-response programs. In the future, information from smart meters could be generated at more frequent intervals to improve these programs. In terms of moving MDM to real-time, Gartner notes that there are not enough implementation sites in production that are able to handle multimillion endpoints with less-than-an-hour interval data, making it difficult to prove product scalability for many vendors. Gartner also notes that there is a lack of data standards and agreed-upon business rules. While this challenge is being addressed with vendors, standards organizations and government participation in standards-setting activities, the implementation of these standards is lagging.

In the final piece of this series we will review implementation sites and draw comparisons to the traditional IT space, with an aim to determine the overall value to the utility, consumer and system.

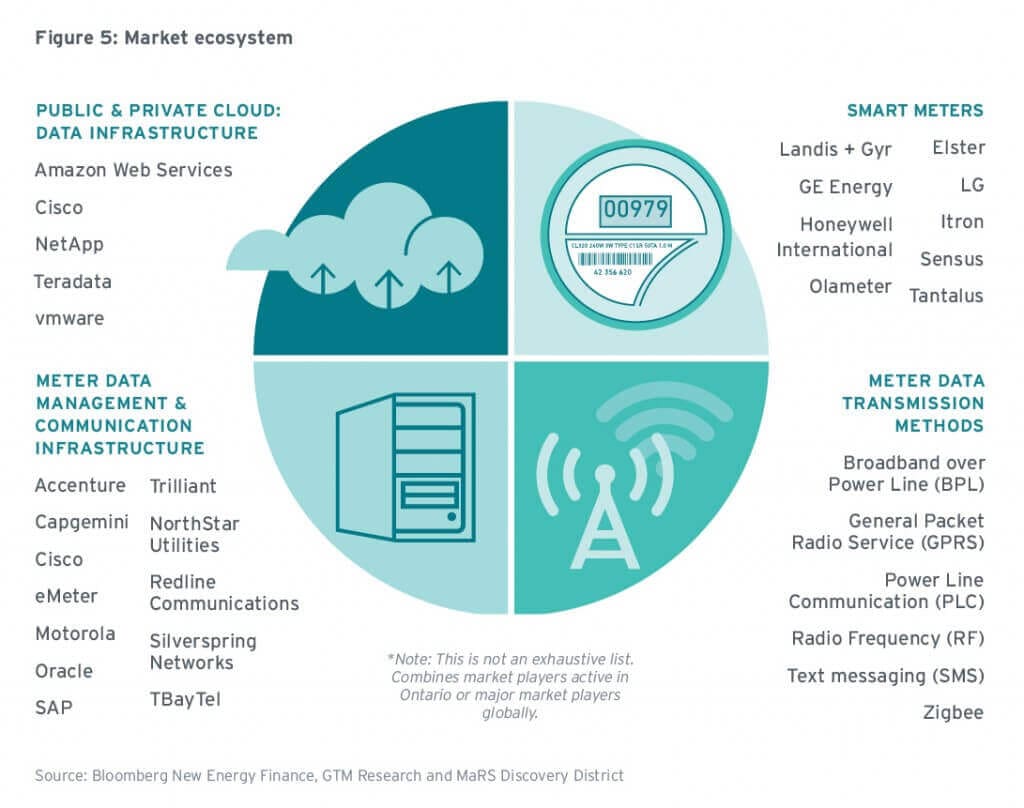

Competitive landscape

Smart meter leaders include Landis+Gyr, GE, Itron, Sensus and Elster SE, with market shares of: Landis+Gyr at 23%, GE at 20%, Itron at 19%, Sensus at 12% and Elster SE at 8%; the remaining 18% includes others and undisclosed.20 Itron is a Canadian leader for MDM,21 and other key MDM vendors globally include Elster Group SE, Landis + Gyr, Oracle and Siemens. The market player map (figure 5, below) highlights these players in relation to those operating in the Ontario market.

The final frontier for information technology

The smart meter is the utility’s gateway to the connected home. Behind the meter, sensors embedded in home technologies (such as appliances, thermostats, and entertainment and security systems) can collect data in real time, thereby allowing consumers to respond to utility price signals, enhance home security and entertainment, and adjust comfort settings.

Smart meters and the data they provide represent an opportunity for the utility to better understand its customer, detect outages, better manage operations (for example, when numerous homes in a neighbourhood charge their cars at the same time), and so on. All of this is an opportunity for the utility to provide services. If utility companies delay in leveraging the information provided by smart meters to offer services to their customers, they could get bypassed by other companies, such as communications or security providers, which already have a presence in the home.

The incentive for a consumer to invest in a smart home goes beyond energy management. Indeed, the value of a connected home is in entertainment, security and in home energy management. This is why Rogers is present in the smart home market, and why Apple has made a move with HomeKit and Google has made a move with Nest. Security companies, like US-based Vivant, are also establishing themselves in the smart home game.

It is these market players—big telecom, IT and security companies—that are challenging the 100+ year utility business model. According to Bloomberg Businessweek, these companies have an advantage because they already have access to their clients’ homes—and those “digital portals” could provide the companies with “back door” access to the retail power market, which is estimated to be worth about US$400 billion. David Crane, CEO of NRG Energy is quoted as saying “When we think of who our competitors or partners will be, it will be the Googles, Comcasts, AT&Ts who are already inside the meter.” According to Crane, the utilities—some of whom struggle to make the best use of the data available—won’t provide much competition. We aren’t worried about the utilities, because they have no clue how to get beyond the meter, to be inside the house.’…”

Energy is just another suite of services these large players can offer—and, much like healthcare, energy is a key vertical that has yet to be transformed by IT. If these major commercial players are allowed to enter the market unhindered, the result could be chaotic. To prevent that “Wild West” effect, utility companies should get involved early, and make maintaining the privacy of their consumers a priority.

[download url=”https://www.marsdd.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Evolving-Digital-Utilty-Final.pdf” type=”pdf”]The Evolving Digital Utility: The convergence of energy and IT[/download]

References

1. Or, as it is defined in Ontario, the functional specification for AMI is the part of the smart metering system between the smart meter and the advanced metering control computer (AMCC) (Electricity Act, 1998).

2. BCC Research. (2013). Enabling Technologies for the Smart Grid. Retrieved from http://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/energy-and-resources/smart-grid-technologies-egy065c.html

3. Frost & Sullivan. (2013). Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure. Retrieved from http://www.frost.com/prod/servlet/cio/246140776 (PDF)

4. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

5. Frost & Sullivan. (2012). Who is Trending in the AMI Market? Retrieved from http://www.frost.com

6. Navigant Research. (2013). Smart Meters. Retrieved from http://www.navigantresearch.com/research/smart-meters

7. Bloomberg New Energy Finance. (2012).

8. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

9. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

10. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

11. BWinfield, M. & Weiler, S. (2014). Working paper: Beyond Smart Meters: The State of Ontario Smart Grid Policy and Practice. York University. Retrieved from http://sei.info.yorku.ca/files/2012/12/Beyond-Smart-Meters-April-28-2014.pdf

12. Information and Privacy Commisioner, Ontario, Canada. (2012). Building Privacy into Ontario’s Smart Meter Data Management System: A Control Framework. Retrieved from https://www.privacybydesign.ca/content/uploads/2012/05/pbd-ieso.pdf

13. Arlitt, E. IESO. (2009). Ontario’s Smart Metering Implementation Program: Lessons Being Learned. Retrieved from http://esr.degroote.mcmaster.ca/documents/1A-1.pdf

14. Information and Privacy Commissioner, Ontario, Canada. (2012). Building Privacy into Ontario’s Smart Meter Data Management System: A Control Framework. Retrieved from http://www.ipc.on.ca/images/Resources/pbd-ieso.pdf

15. Norman, J. Ministry of Energy. (2011). Presentation: The Green Energy Act and the Smart Grid in Ontario. Retrieved from http://energy.mcmaster.ca/CES_presentations/green_energy_act_NORMAN.pdf

16. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

17. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

18. Arlitt, E. IESO. Ontario’s Smart Metering Implementation Program: Lessons Being Learned.

19. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

20. Bloomberg New Energy Finance. (2013).

21. Frost & Sullivan. Smart Metering Focus: Advanced Metering Infrastructure.

The Connected World Market Insights Series

The Connected World Market Insights Series will cover such topics as:

- Advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) and smart meters: Building upon a home advantage

- Automation and energy: Unlocking home and building energy management opportunities

- Entertainment for the connected home

- Security: Privacy, data ownership and data risk

- Transforming health: Decentralized and connected care

- Connected mining opportunities and new technologies

- The value of real-time meter data

We’ll highlight the innovators in industry, academia and government throughout this series. In fall 2014, we will cap the series with HomeConnect 2014. This event will feature some of our companies, alongside major industry players, as they showcase their technology and solutions.

Accessing data is key, but we think that being able to format and analyze that data is where the real value can be found. During this series, MI will delve into the market opportunity now becoming available due to progress in opening up datasets, and the development of infrastructure and analytics that are creating new services and products and bringing them to market.