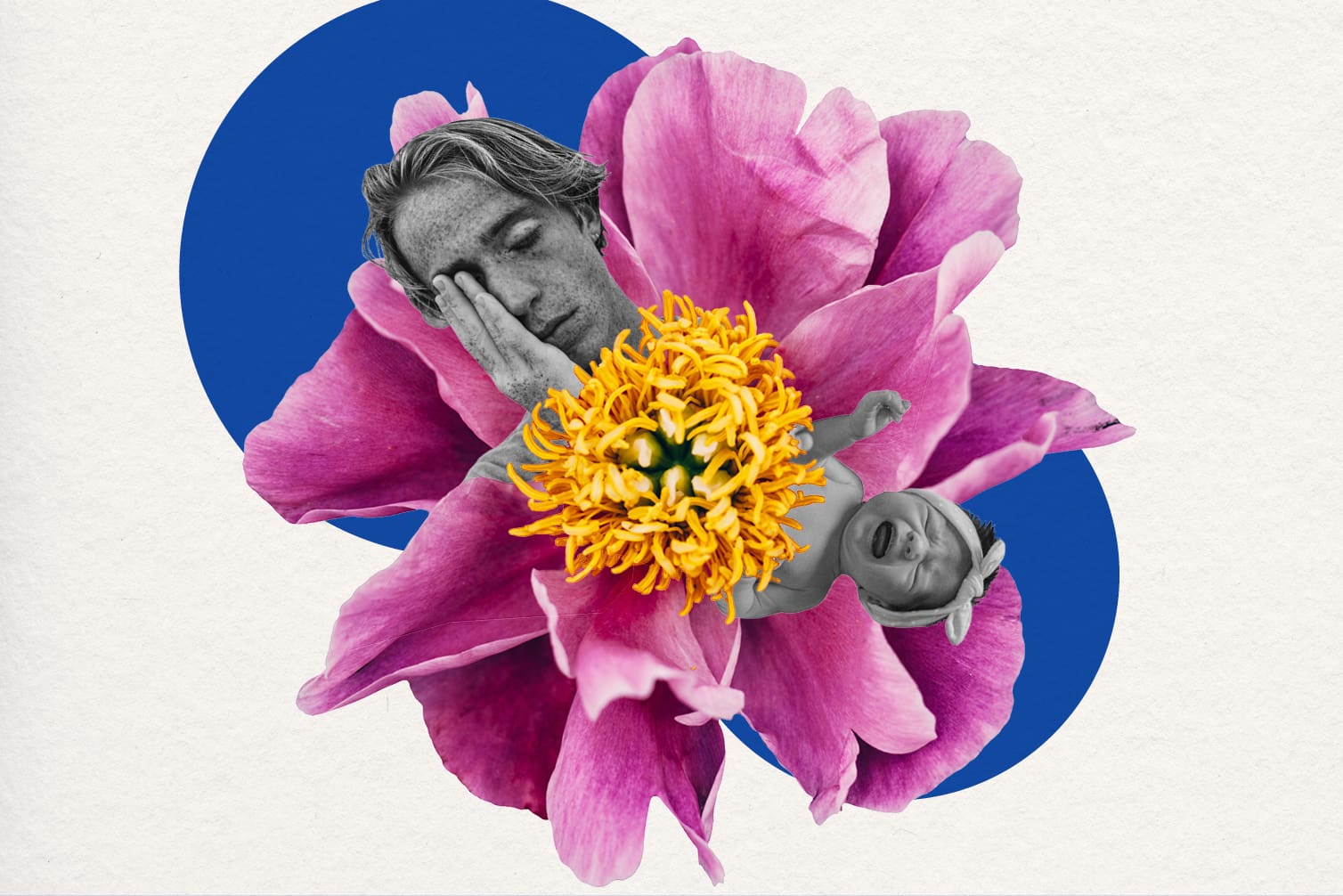

How tech tools can provide a lifeline for new parents

By Rebecca Philps | June 13, 2024

For anyone struggling after having kids, finding the right support can be a challenge. With new online platforms, help could be a click away.

When Patricia Tomasi began experiencing panic attacks and intrusive thoughts when her second child was three months old, she headed to the ER, hopeful that she might find help. “I could feel myself slipping into and out of reality,” she says. The experience was a familiar one: After the birth of her eldest three years earlier, Tomasi developed postpartum depression and anxiety, which eventually became full-blown psychosis. She made it through, but she and her husband were on high alert for telltale signs — a crushing sense of anxiety among them.

ER staff said Tomasi’s blood tests were normal and there wasn’t much they could do — she was instructed to go home, rest and follow up with her general practitioner. Thankfully, bolstered by a supportive partner, a sympathetic receptionist and her own experience, Tomasi managed to book a next-day appointment with her primary care physician, who prescribed an SSRI. Within a few weeks, things began to improve. While it took months to see a specialist, Tomasi got the help she desperately needed.

For many new parents without the access and awareness to tackle the range of mental health challenges that can accompany building a family, that support can seem impossibly out of reach — especially during a time of massive upheaval. But digital tools — accessible anytime and anywhere, providing expert advice and a vital connection to community — can be a lifeline for parents who are overwhelmed, potentially isolated and most definitely sleep-deprived.

The reality of perinatal mental health

While people may talk about baby blues, there is a full spectrum of mental health conditions that affect the mood, behaviour, wellbeing and daily function of an expectant or new parent. Perinatal mental health disorders, or PMHDs, are characterized by distressing feelings that range from mild to severe during pregnancy and throughout the first year after birth. These conditions can include depression, anxiety, panic disorder, OCD and psychosis.

The numbers are significant. In Canada, between 20 and 25 percent of mothers experience PMHD. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this increased to one in three women for depression and one in two women for anxiety. Non-child-bearing parents, including those who create a family via adoption, fostering to adopt and surrogacy, can experience PMHD as well. Rates are higher for marginalized people, and Indigenous mothers are 20 percent more likely to suffer from prenatal and postpartum depression than Caucasian mothers in Canada. Any new parent who has experienced mental-health disorders is at an increased risk of relapse.

There are a host of reasons people might be reluctant to report psychiatric symptoms. Some feel ashamed of negative feelings about pregnancy or parenting. Others worry what people might think of them, or that they will be deemed unfit. Indigenous and racialized mothers have been disproportionately affected by birth alerts (when social workers or hospital staff raise concerns about an expectant parent) and though most provinces and territories have outlawed that practice, the harmful stereotypes that fuelled it remain. There are also the moms who under-report simply because they are unsure whether or not their symptoms are part and parcel of the process of becoming a parent.

“When you have a mental health issue, it’s hard to even recognize what’s happening,” says Tomasi. “Maybe you think you’re overwhelmed with motherhood or you’re just sleep deprived. You likely don’t understand the full complexity of the biopsychosocial mechanisms involved in having a perinatal mental illness. And if you do present yourself to a doctor, midwife or obstetrician, you just hope that that medical professional has either heard of perinatal mental illness or has some training, which more often than not they don’t.”

While Erica Djossa spent hours preparing for labour and delivery, the psychotherapist and mom of three never had the opportunity to discuss or brace herself for the emotional roller coaster and wild adjustments she’d have to make in her new parenting role. “When new parents start to experience negative emotions, they often think the problem is with them, that they aren’t cut out for it,” she says. “And with that comes incredible shame.”

Finding support to open up about struggles

For Canadians experiencing infertility, who may also be using reproductive assistance or forming families with the help of adoption and surrogacy services, navigating the attendant medical, financial and legal complexities can be a huge mental load. And if those new parents are also grappling with PMHD? “It’s awful,” says Jackie Hanson, founder of Sprout, a family-building and fertility benefits virtual care platform. “All they wanted was to bring home a baby. The time, the money, the effort. And then they feel so guilty and ashamed that they’re struggling. But mental health challenges are common for all new parents.”

Embracing all pathways to parenthood is fundamental to Hanson’s life story: she and her twin sister were born through IVF in 1994. Employers who purchase Sprout’s benefits package for their employees can unlock access to a library of resources and a list of vetted providers, like fertility and surrogacy clinics and therapists who specialize in supporting people who become parents in non-traditional ways. “We want to make sure that regardless of how people are building their families, they have access to someone who understands the specific challenges they’re facing,” Hanson says. Adoptive parents may have concerns about how quickly they are bonding with the baby, or anxiety over being monitored by social service agencies; folks who struggled with infertility and experienced miscarriages may feel as though they’re navigating a minefield of potential problems throughout the prenatal period.

Before she became a mom, Djossa trained as a psychotherapist and worked as a clinician for nearly a decade. “You’d think I’d be prepared for the realities of new parenthood,” she says, “and yet I was totally blindsided by my own postpartum depression and anxiety.” She began unpacking her experience on Instagram, candidly sharing her struggles and what she was learning. Djossa wanted to normalize conversations about perinatal mental health and provide educational content on social media — to intentionally meet new parents where they are at. Her Momwell platform now offers workshops and access to virtual therapists who specialize in perinatal mental wellness. “All attention centres on the baby postpartum. Moms get one checkup, and then parents fall off of a care cliff.” Momwell offers workshops and courses on crucial pain points, such as the division of household labour, postpartum anger and stress around return to work. “We want parents to know: You’re not broken. There is a solution here.”

Virtual resources allow parents to privately explore sensitive subjects they may not be ready to talk about with friends or family, or even admit to themselves. They can access the content at any time (which feels particularly welcome after a dreary middle-of-the-night feeding session) and, most importantly, they can see they’re not alone. This is a gift for parents who may be struggling to make connections in their community, or who live in remote areas without access to support centres.

How to keep new parents talking

Talk therapies are known to be among the most effective interventions in mental health for depression and anxiety. But due to a dearth of available specialists and cost barriers, fewer than 10 percent of perinatal populations have access to such resources.

Daisy Singla, an associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, wants to address that gap. To that end, she’s examining ways to improve access to mental-health care for pregnant women and new parents through the Summit Trial, a four-year, four-city study wrapping this May. The study focuses on two key innovations. One, task-sharing, involves “training people with no prior mental health background or experience to deliver talk therapies,” she says. The second area is telemedicine, which will be used to deliver support. As Singla explains, the goal is to determine whether these two approaches can be as effective as specialists and in-person care. If her hypotheses hold, they could be evidence to argue for an efficient, affordable and accessible stepped-care model, where non-specialists such as nurses provide online talk therapy, while those who require more intensive intervention can see specialists.

Unlike the U.K., U.S. and Australia, Canada does not have a national perinatal mental health strategy. What’s more, access to perinatal mental health services varies wildly across the country. In 2019, Tomasi co-founded the Canadian Perinatal Mental Health Collaborative (CPMHC), and right away they went big, demanding a federal strategy for timely access to perinatal mental-health services. They’re still waiting for that strategy, but this fall, researchers affiliated with CPMHC, in conjunction with Women’s College Hospital, will release Canada’s first clinical perinatal mental health guidelines for The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).

“It’s a critical first step,” says Tomasi. “It will help doctors and midwives and obstetricians detect and treat perinatal mental illnesses so that we’re not just being reactionary, so we can actually work on prevention.” The goal is for every parent to have universal screening for PMHD starting in preconception, and continuing through pregnancy and the postpartum period. This is crucial, because studies show that children who are born to parents with an untreated perinatal mental illness are at much higher risk of developing behavioural problems and mental health issues as they grow.

Tomasi is hopeful that perinatal mental health awareness will extend beyond the bubble of those who’ve been affected by the experience. “This is an issue that can happen to anyone in any demographic, any race, culture, religion,” she says. “This illness doesn’t discriminate, and it’s so important for families to get treatment — for the well-being of future generations.”

Photo illustration: Stephen Gregory; Photos: Unsplash

Rebecca Philps

Rebecca Philps