Heat warning: Are we ready for a hotter climate?

Extreme heat waves are becoming more frequent and intense. The UN’s chief heat officer warns we can’t — and shouldn’t — air condition our way out of this crisis.

Extreme heat waves are anything but normal, but they’re quickly becoming the new reality. The 10 hottest years on record have all happened in the last decade. And because temperatures in urban centres can be 10 to 15 degrees Celsius higher than surrounding areas, cities can be dangerous places to be when the mercury rises — particularly for the elderly, those with pre-exisiting health conditions as well as poorer populations who lack access to air conditioning. “Heat has a way of going through the city and finding those who are the weakest,” says Eleni Myrivili, the United Nations’ global heat officer. “It’s a very unfair climate condition.” In this episode, we explore the growing risk posed by heat and what could help us adapt to a hotter world.

Featured in this episode:

Further reading:

- What will it take to save our cities from a scorching future

- Earth’s 10 hottest years on record are the last 10

- Extreme heat is deadlier than hurricanes, floods and tornadoes combined

- Heat inequality ‘causing thousands of unreported deaths in poor countries’

- The heat crisis is a housing crisis

- Ancient civilizations countered extreme heat. Here’s what cities borrow from history

- Toronto’s getting hotter. Experts say a chief heat officer could help the city adapt

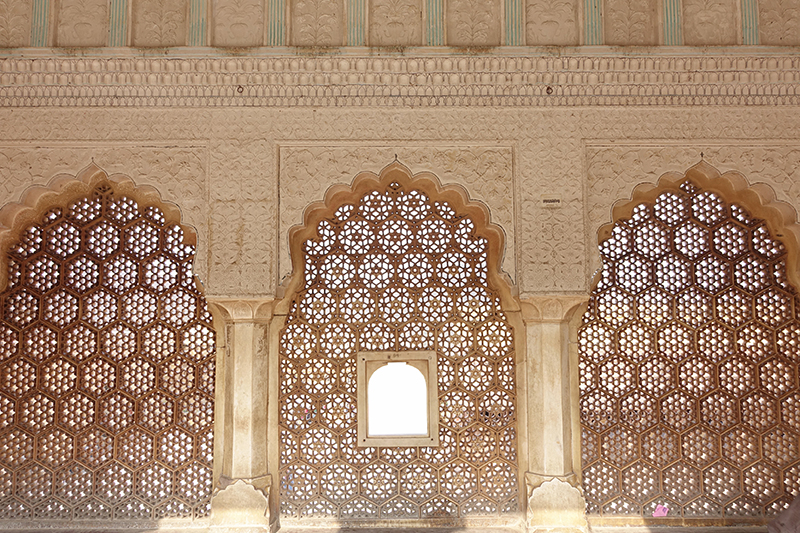

- Architects turning to India’s lattice-building designs to keep buildings cool without air conditioning

- How India’s lattice buildings cool without air conditioning

- Athen’s answer to a water supply crunch: an ancient aqueduct

Subscribe to Solve for X: Innovations to Change the World here. And below, find a transcript to “Heat warning.”

Narration: I’m Manjula Selvarajah. This is Solve for X. Today, we’re going to get into extreme heat. 2024 was the hottest year ever recorded. That comes after a decade of even higher temperatures. But this is a record we can’t keep breaking.

Eleni Myrivili: You know, Manjula, it’s not just heat. Because I think of heat as, like, the beginning of it all, in a sense.

Narration: That’s Eleni Myrivili. She’s the world’s leading expert on heat in cities.

Eleni Myrivili: The fact that we’re heating up our planet expresses itself in all these different extreme phenomena.

Narration: In 2022, the United Nations named her the first ever global heat officer. And before that, she was the chief resilience officer for Athens, Greece.

Eleni Myrivili: When I talk about heat, I often talk about heat as global warming, but also, what does that mean on a very local level? And that, of course, means heat waves, but it also means tons of other extreme weather events.

Narration: We don’t have a chief heat officer in any city in Canada yet, unlike Miami in the U.S., Santiago, Chile and Freetown, Sierra Leone. But extreme heat is becoming a serious concern here, too.

Eleni Myrivili: In 2021, the Pacific Northwest had this incredible heat wave. I remember the city of Lytton, I think it is in Canada, that, after a long period of extreme heat, it burned down.

Narration: Lytton and other areas in British Columbia suffered abnormally high temperatures that summer.

Eleni Myrivili: It was the first time that we started hearing about this heat dome effect.

Narration: The day before the fire, it reached 49.6 degrees Celsius. That’s over 20 degrees higher than normal — the highest temperature ever recorded in Canada. It’s a scary preview of how dangerously hot our climate is becoming. And with urban areas around the world expected to warm even faster in the coming decades, cities are on the front line.

This is my conversation with the UN’s chief heat officer, Eleni Myrivili.

Manjula Selvarajah: Now we’ve reached you in Athens today, is that right?

Eleni Myrivili: Yes.

Manjula Selvarajah: And Greece has seen…. It has seen hot days; it’s seen heat waves. And what the city has, or Greece has, is this category system for heat waves from zero to three, with three being on the top. Have you ever been in the city during a category three heat wave?

Eleni Myrivili: We had a few days that were category three, both in 2024 and in 2023 and in 2021.

Manjula Selvarajah: Can you describe to me what it feels like to be in the middle of that?

Eleni Myrivili: It feels breathless, like, it feels like you can’t really breathe because it’s so hot, and it feels like you don’t really want to do anything. It’s just… it’s really difficult to get motivated to do things.

Manjula Selvarajah: How hot does it get?

Eleni Myrivili: I think it got up to 45 degrees, 44, 45 degrees in Athens. But there are other parts of Greece that got, I think it went up to 46, 47 degrees Celsius. But for a lot of people, what this means, especially people that are what we call the vulnerable population, it means that they can get really, really sick and end up in the hospital, or even, you know, die from it. Any kind of pre-existing conditions, we see people with extreme symptoms end up in hospitals, including mental health conditions. Like everything, kind of, our bodies…

Manjula Selvarajah: It’s like amplified.

Eleni Myrivili: Yes, get out of whack when we’re dealing with extreme heat. So this is the weird thing about heat, that it has a way of going through the city and finding who are the weakest people and the most — the people that are the most poor, actually.

If you are upper class or upper-middle class, you can, you know, leave the city, you can have air conditioning on, you can work from your job that’s on a computer — and not manual — in an office that is, you know, cooler or, you know, whatever. It’s really… . And this is really what I find very painful about this part, this particular kind of extreme weather, because it really targets the weakest. It’s a very unfair climate condition.

And the other, of course, vulnerable populations are the people that are workers, either in agriculture or construction or any kind of physical work. It’s really difficult, and the problems that we often have there is that we have work-related injuries. There was a report that came out, I think two or three years ago, where they examined 11 million cases, and then correlated them to the temperatures of the days that these injuries were reported. Then there was a very direct correlation.

Manjula Selvarajah: You know, part of what you’re talking about is the health portion is really important, but there’s also this impact to the economy, and I would also imagine that there’s also an impact to infrastructure, right?

Eleni Myrivili: Yes.

Manjula Selvarajah: That there are some systems that just can’t function at those temperatures.

Eleni Myrivili: Absolutely. Manjula, you’re absolutely right. I mean, if we go into the economies of cities, they do indeed suffer, and we know how much we lose in GDP during the days of extreme heat. As far as infrastructure is concerned, we do have problems on a lot of different systems. So we know that train tracks buckle, we know that our phones and communication systems have trouble working. You know, our phones, after a specific temperature, they stop functioning, they go black, or our computers, they also go down. But we’ve had problems with asphalt in some countries, depending on the mixture of asphalt they have, because it starts getting kind of soggy and sticky. We have problems with bridges. Like in England, when they had the heat wave in 2022, they had to cover a whole bridge, which was, I think, it was made out of steel. I don’t know what kind of material, but some kind of metal. So they covered it…

Manjula Selvarajah: To cool it down?

Eleni Myrivili: To cool it down so that it didn’t absorb heat from radiation, yeah.

Narration: Buckling train tracks. Melting asphalt. During extreme heat, cities are grinding to a halt and becoming dangerous places to be. This feels like uncharted territory. We’re seeing records being broken in terms of high temperatures in cities around the world. But how else is heat changing as a result of climate change?

Eleni Myrivili: Well, we do have much longer periods of heat waves. For example, in southern Europe, the summer of 2024, we had 66 days of extreme heat stress. It’s called UTCI, which doesn’t only measure temperature, but it also measures relative humidity. So it kind of gives you a better sense of the comfort of the body, right? So we had high stress conditions for 66 days, when the average we’ve had for the last decade was 29. So that just goes to show you how it’s more than doubled. and how this is really changing the way we experience it, right? Because it’s longer and it feels like there’s no respite. It feels like you can’t escape it. You wake up every day, and again, you deal with this unbearable kind of sense of heat that… That’s the other… I was thinking as you were talking Manjula, that it’s so difficult also to describe it. You asked me before, how does it feel to be in a city of 45 degrees? I can’t, I don’t know how to describe it. Like I… it’s not so easy to describe it. So anyway…

Manjula Selvarajah: Is it? You know, I imagine that you can’t sweat. You feel sluggish, right? I mean, I feel that on even slightly hot days out here.

Eleni Myrivili: Headaches, also. You feel like you’re a bit confused — your thoughts are not clear, you get sluggish. It’s just a condition of general malaise, of discomfort, of intense discomfort.

Manjula Selvarajah: And in some way that you’ve described it, we’ve talked about how heat discriminates. It’s also sort of silent in the way that it affects people.

Eleni Myrivili: Yes. And that’s why we call it the silent killer. I mean, this is what we’ve been calling heat, because all of these things that we’ve been discussing right now is like the fact that, in a way, heat has no representation. It’s hard for journalists to show images of it. It’s hard for people to talk about it. The impacts are not visible. The impacts are not even knowable, often, because, again, there’s no data, often, that is immediately available. So the whole thing is like this weird, ghostly presence that actually attacks our weakest.

Manjula Selvarajah: Why is this so difficult to track?

Eleni Myrivili: To a large extent, because a lot of problems are not caused directly by heat. Like, the people that actually die from heat stroke is a very, very small percentage of the people that lose their lives because of heat. So people, for example, as we said before, with heart problems, when they go to the hospital, and if they lose their lives, the hospital doesn’t say that, “You know, it was a hot day, or it’s probably linked to the fact that it was a heat wave.” They just say that it was cardiac arrest. So most of the victims of heat are not reported as such. So we have to find other ways of counting them, and that has been a challenge.

Narration: I find it interesting that Eleni’s background is in anthropology. But it makes sense. To adapt to an increasingly hotter planet, we need experts of all kinds: scientists, urban planners as well as anthropologists who can help decode our social structures and devise ways to shift behaviour.

Manjula Selvarajah: You know, I look across Canada here, I mentioned to you that we identify ourselves, we see ourselves as a cold country, right? And one of the things that happens is when the weather gets slightly warm, the sandals come out, everyone heads for the sun.

Eleni Myrivili: Yeah.

Manjula Selvarajah: I just wanted you to kind of reflect on this idea that we have these cultural understandings of heat. Does that affect our ability to, you know, to adapt our readiness? Does it affect that?

Eleni Myrivili: Absolutely. This is crucial, what you’re saying. Because what we need to do is we need to change behaviours, right? We have to kind of decide, each of us, that we have to do things differently because of extreme heat. And that is often really, really difficult. People in cold countries feel that heat is a wonderful thing, and they all kind of go outside and they spend as much time as they can to kind of luxuriate in the sun and in the heat, so they don’t understand how dangerous it is, and they are not willing to see it as a danger because they’ve been programmed to see it as something that’s absolutely delightful. And it’s really hard to get them to feel the risk in it.

On the other hand, for countries where they’re used to heat, people feel like, well, “We know this. This is not a big deal. We’ve been dealing with heat for a very long time, and this is just a little bit more hot. So how bad can it be?” All of these different symptoms come on very fast, and it’s really, really, unless you really know what’s going on, it’s really difficult to identify. Water often isn’t enough. We have to kind of move the person to the shade, call an ambulance as soon as possible if we see somebody losing their consciousness, et cetera, et cetera. So it’s not just for us, but also, if we want to help other people, we have to really start learning the symptomatology and learning what we should do. And this is not common knowledge yet.

Manjula Selvarajah: One of the things that you’ve advocated for is naming heat waves. Can you explain that idea there?

Eleni Myrivili: I always felt the categorization of heat waves is actually more important than the names of heat waves. I think that what naming does is like taking it a step higher, because it makes heat waves into an entity. And we tend, as humans, going back to the anthropological kind of side of things, we tend to, humans, to take entities more seriously than things that do not have, like, a name, right? Things that have a name actually are more. They exist more so…

Manjula Selvarajah: That is so true. Because I can still, you know, I think of Hurricane Katrina, and I can think of the effects around it exactly, and how so many other things were blamed on it.

Eleni Myrivili: Exactly.

Manjula Selvarajah: Yeah.

Eleni Myrivili: My daughter, who is 25, was telling me the first time that she heard, because it was in Seville a couple of years ago that the first heat wave was named, I think it was named Zoe, actually. There were a lot of people advocating about naming, but I wasn’t really persuaded. And then my daughter suddenly said that when she heard the name Zoe for a heat wave, she got extremely sad, and kind of, it was like it moved her emotionally, because she felt that it was suddenly something that was not just a fleeting thing, or, you know, heat was kind of rising or whatever, but it actually it had, like, an emotional effect on her, which really surprised me. I really didn’t expect that, but I think that that’s part of it, like, the whole idea of anthropomorphizing something, of giving it the name, it can actually affect us in ways that are much stronger.

Manjula Selvarajah: And maybe on a municipal level, or even at an individual level, it makes you do things. Like you might decide that, “Oh, I’m going to cancel that outdoor wedding,” or “I’m going to make sure that my neighbors don’t go for a run,” or a city may decide that this might not be the day that we go out and do this big construction activity, whatever it is. So it drives that kind of behaviour, too.

Eleni Myrivili: Precisely. That’s the idea.

You know, we are talking about the hottest years ever recorded, 2023 and 2024. And if you see it in charts, you know, you see the years for 1850 going kind of a little bit higher, a little bit higher, a little bit higher in temperature. And then suddenly you have 2023 and 2024, like, go off the charts and, like, with a big distance from the previous things. And then you look at CO2 emissions, and they’ve been going up. Like the curve is going increasingly up. It’s not curving downwards. And I don’t know, I think people kind of feel like we are kind of putting a cap in our CO2 emissions, that we’re doing a little bit better.

Truth is that we are doing better in the sense that we have included much more renewables in the mix. But the CO2 is still going up, even though we’ve put the renewables in. So demand for energy has increased very much because of heat, as we were saying before, people need more units of AC units, and because of data centres, actually, which are guzzling up a lot of our energy. But basically, it’s more… and it’s going up. I think we have to go more radical, because nobody’s actually moving.

Manjula Selvarajah: So Eleni, let’s talk about solutions. You’ve talked about air conditioning as being this egotistical solution. What do you mean by that?

Eleni Myrivili: Well with air conditioning, we cool ourselves, or we cool our house or our office, and then it radiates heat… not radiates, it pushes out heat into the public space, so it ends up heating up the public space even more. So people need to use more air conditioning, or people that don’t have air conditioning suffer from much more heat. We need to understand our cities like little systems. So you have to kind of figure out how to make the public space cooler so that the buildings need less mechanical cooling.

Ideally, you also need the buildings to be built in ways and to be designed in ways that have passive cooling elements. And you could do that in retrofit, but I think the best way to think about these passive cooling elements in buildings is to think about air moving so to think about creating cross ventilation, or other ways of ventilating, which, you know, is very interesting. And we know a lot about this from the way that people used to…

Manjula Selvarajah: Used to build houses. It’s so interesting that you say that. You know, I was brought up in Sri Lanka, and I remember as a child going up to northern Sri Lanka to a place called Jaffna, which is a city up there, and going back to sort of the ancestral home. And I mean, all it had was the occasional fan. But fans are also expensive because they need electricity.

Eleni Myrivilli: Right.

Manjula Selvarajah: So you would have houses with atriums in the middle and sort of, like, lattice screens everywhere. You would have bricks, but then the bricks would have sort of, like, holes in between and…

Eleni Myrivili: Manjula I love to hear this. I really love to hear these kinds of descriptions of these buildings that actually were built with this incredible traditional knowledge of being adaptive to the local climate conditions, right? I mean, centuries of knowledge had gone into this vernacular architecture exactly because we didn’t have fossil fuels, and people built houses based on how they can cool themselves and heat themselves in more like passive ways. And you know this idea of having a central atrium, of having these lattices, of having these holes in the walls, of having white walls, or white kind of roofs, or, you know, all these things that are so… I find also so beautiful.

Manjula Selvarajah: They are beautiful.

Eleni Myrivili: They’re so beautiful, right? I mean, I can, like, having a central little garden with elements of water in a house that’s built around it is such a beautiful thing. People gather there. It kind of creates a cool atmosphere. It’s like, it’s brilliant. We’ve gotten to this modernist architecture, which not only, I mean, it had its logic and it was a democratization of things and that. I mean, I don’t want to be ranting on it because, of course, it actually had the amazing positive elements. But right now it’s not really good for us anymore. We have to go back to other ways of building and other ways of understanding.

Manjula Selvarajah: But how do you do that in a city? Like, how do you… what are some ways? I mean, you have the experience from Athens as well, right? It can’t just be lattice screens, right?

Eleni Myrivili: It can be lattice screens, though, to a large extent. I mean, a lot of it has to do with shade. So we have to understand that shading really, really changes the comfort of our bodies, either indoors or outdoors. So we have to make sure that we have a lot of shading elements. So that’s something that we could do. You could put extra shading and stopping the heat coming in. Another thing is we have to make sure that we create openings, as you said. We have to make sure that we understand how heat moves upwards, right? And this, I think, will become more and more second nature to us as we move into decades that are hotter. So this knowledge that our grandparents and great-grandparents had is going to come back to us, I think.

Narration: I was struck by what Eleni said about the power of design. Those lattice shades I grew up with? If you haven’t seen them, they can be built right into the facades of buildings, or they could be in place of a window with simple slats or gorgeous wood carved openings letting the breeze in while blocking the sun’s rays. Compare that to how we build today, with lots of glass and concrete, creating what’s known as the urban heat island effect. Studies show that urban spaces can be 10 to 15 degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas. And even within the city, depending on the neighbourhood, how wealthy or green it is, temperatures can vary widely.

Eleni Myrivili: And you know, Manjula, even a couple of degrees less can make an enormous difference, like two or three degrees less heat is enormous. It’s really big for our bodies.

Manjula Selvarajah: And there’s a place for policy-makers too here.

Eleni Myrivili: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Manjula Selvarajah: We’re not talking about the individual homeowner. We’re talking about roof gardens. We’re talking about more parks, which is, these are some of the changes that you made in Athens.

Eleni Myrivili: So a big, big part of how policy-makers can make a difference is how to make the public space cooler. And this has a lot to do with bringing more nature in the city. This is, like the number one most important and most significant and most effective way of cooling cities, making them much more — and I don’t mean a little bit, like adding a few trees here and there — I mean significantly bringing trees in our cities. And how can we do that? To a large extent, again, unfortunately, our policy-makers have to get rid of cars, because a lot of our public space is dedicated to cars, to private cars. Give a lot a big chunk of what now is our public space, instead of to cars to both slow mobility, which is, you know, moving, walking, bikes, of course public transportation, and ideally, electric public transportation.

And then we need to do legislation for buildings. As we have, for example, for earthquakes, the word escapes me right now, but rules of how we build and what actually is acceptable in relation to heat, which we don’t have.

Manjula Selvarajah: Because you’re right, right now, if you think of a place like Tokyo, you know, you have to build earthquake-proof buildings. So in a way, what you’re talking about is, I don’t know if heat-proof is the right word, but, but I think what you’re saying is…

Eleni Myrivili: Heat-proof.

Manjula Selvarajah: Heat-proof.

Eleni Myrivili: Increasingly, I’m realizing that the most important thing, more than anything else, is water when we’re talking about extreme heat. And that cities have to think first and foremost about how to create more robust… have more backup systems.

Manjula Selvarajah: Why is that? Is it because you’re thinking of them as heat sinks? Is that why? Why water?

Eleni Myrivili: We’re constantly realizing that if nature is our main weapon against extreme heat in cities, nature needs water, and that is what will keep it alive, and that is what will stop it from just shutting down and being extremely stressed or even dying. And a lot of cities don’t prioritize, of course, irrigation when there is a period of drought or a period of extreme heat. And this is really, really, really significant, because we know that around the world, water is becoming more and more an issue, more and more of a resource that we are seeing being depleted.

Manjula Selvarajah: Now, because you mentioned water, I have to selfishly ask you this, because this is actually, I think, very cool. I heard that you worked on an… there’s this old Roman aqueduct that runs under? I mean, tell me about this. Tell me about this Roman aqueduct under the city of Athens.

Eleni Myrivili: Yes. So it’s 24 kilometres long, and it is running underground. It was built, as you said, during Roman times. I mean, it’s really, really, it’s unbelievable. How did these people build it? They actually built it with a perfect incline for 24 kilometres, so that the water doesn’t run too fast at times, nor too slow and kind of become stagnant. It’s perfect.

Manjula Selvarajah: And it’s in good shape?

Eleni Myrivili: And it’s in really good shape, and it has been interrupted by, I think, a subway line and a couple of roads and stuff like that, but it still has the capacity to move water. I think it’s close to a million cubic litres per year that goes through it. So it’s kind of a lot. So now the metropolitan area, the region of Attica, has decided to actually tap into it and use it for irrigation. And this is really, really amazing. I mean, it needs. It will have a little bit of processing, but it will basically go to irrigate parks — new parks and existing ones — and creating a few water features also on the surface to help cool this. It goes through nine different municipalities of the metropolitan area, so I’m really looking forward to seeing this starting to be implemented.

Manjula Selvarajah: That’s Incredible. And it comes back to what you were saying with that idea that water now in the city actually keeps these green spaces alive and functioning at times where, I mean, you’re going to have a heat wave again this summer, a couple of heat waves potentially this summer.

So when you think of the moment that we’re in now, how do you think that future generations will look back at it?

Eleni Myrivili: I think they will think that we are, we were really stupid. And I think they’ll hate us for it. I think that they won’t be able to understand how, if we had the knowledge we hadn’t been acting on it. This is why I think they won’t forgive us.

I don’t even understand why we haven’t been acting on it. It’s difficult. I mean, I do and I don’t. But it’s difficult to fathom the fact that there isn’t enough urgency built to our change of behaviour and change of policy.

If we know that water is becoming more and more scarce, like in my city, we are really facing extraordinary problems of lack of water in the next couple of years. There’s no campaign telling us to try to economize. There’s no effort, globally. We’re flushing clean water, drinkable water, down our toilets every time we go to the bathroom. It’s kind of insane. And we say that people in the future will think of that and say that we were absolutely mad. Or, you know, the way that we build our buildings that are so dependent on air conditioning and they don’t have even windows — you can’t open a window. They’re all, like, locked in these glass buildings that are so wrong for our climates. All of these crazy things that we haven’t, like, changed policies to adapt to our changing conditions, and we are being really foolish in the way that we are… We keep on going like nothing’s different.

Manjula Selvarajah: But there’s some hope there, too. I mean, take even the role that you have. The fact that you, there exists now a UN heat officer, and the fact that there is a handful of cities, I think there’s probably about 12 cities in the world that have heat officers now, I think that’s meaningful because it shows that some of these cities have decided that this is a problem and that we need a person devoted to it.

Eleni Myrivili: True. That is very true. And there’s more and more. I think the last two or three years have been really, have really changed the way that we understand and the way that we have been dealing with heat. And I see extraordinary difference. Like from 2021 to 2025, the amount of heat action plans and the amount of early warning systems, and the way that these issues are being communicated is night and day. What we haven’t been working on as much is the design, the redesigning of our cities and actually bringing more nature into the cities. If we see it globally, it’s actually the nature in cities is still diminishing. So we have to really step on that. We have to understand that this is crucial, and we have to make sure that both nature in cities, but also forests outside of cities, is something we have to support and create more of.

Manjula Selvarajah: What do you think the role of technology could be here? Is there anything exciting that could help address this problem?

Eleni Myrivili: Absolutely. There’s tons of technologies that are, right now, coming up that could be from the materials that we build the houses or that we cover our homes with, or, you know, that we, I mean, paint our homes with, like reflective paint that is cutting-edge right now, and it’s something that could really make an enormous difference. So that’s one aspect, but also technology can better assess where we can prioritize our solutions to make sure that we protect the most vulnerable. So this is another part that data and technology is really helping us with.

Manjula Selvarajah: So it’s like predictive, is it predictive analytics?

Eleni Myrivili: It’s predictive.

Manjula Selvarajah: Is that what you’re talking about?

Eleni Myrivili: It’s predictive or it’s real time. It can also, we have, for example, some AI applications that we have seen in cities in India, where they can do super-local solutions of assessing in real time which buildings that are most hot at the moment to inform the people to kind of move in cooler buildings or in cooler parts of the city. So all of… there’s like so many things happening through technological innovation. It’s very promising, and I’m very hopeful.

Manjula Selvarajah: One of the things that I’ve found quite interesting, I’ve seen it, I’ve heard cases of it being used in healthcare, but it’s this idea of the digital twin, right?

Eleni Myrivili: Yes.

Manjula Selvarajah: I don’t know if that’s something that excites you as well.

Eleni Myrivili: It can be very exciting.

Narration: If you haven’t heard the term before, a digital twin is essentially a virtual replica of a real world system that could be a body, building, or even as big as a city.

Eleni Myrivili: As long as we don’t overdo it. Because with digital twins, sometimes people get over excited to create a duplicate of reality, and often we don’t need all this information. Like, digital twins can work in very targeted ways. So often, scientists and technologists get really carried away and kind of try to create these enormous things and more data, and more data, and more data that are not really useful. Like, this is why it’s important to get scientists and technologists and data providers and creators to work closely with cities and with communities so that they don’t go off on their kind of crazy scientific journey.

Manjula Selvarajah: Yeah, it’s very pragmatic.

Eleni Myrivili: Yes, we need them to be a little bit more linked to reality and to what people need, because we need solutions fast and we need them now.

Manjula Selvarajah: Eleni, that was such a fascinating chat. Thank you, and thank you for telling me about the aqueduct.

Eleni Myrivili: Oh, thank you. Manjula, thank you so much. Thanks. Thanks for this interview. It was great fun to talk to you.

Narration: It’s clear that our cities are heating up, and that’s going to change the way society works. We can’t air condition our way out of this. In the next episode, we’ll take a look at some of the technical solutions innovators are working on to help keep us cool. And if you want to see photos of the architecture in the city I grew up in, and the Roman aqueduct Eleni helped repurpose in Athens, you can find all the details in the show notes.

Solve for X is brought to you by MaRS. This episode was produced by Ellen Payne Smith. Lara Torvi and Sana Maqbool and Sarah Liss are the associate producers. Kathryn Hayward is the executive producer. Mack Swain composed the theme song and the music in this episode. Gab Harpelle is our mix engineer. I’m your host Manjula Selvarajah.

llustration by Kelvin Li; Image source: iStock

MaRS Staff

MaRS Staff