The pandemic’s impact: 1 million jobs have already been lost

New data confirms the just how badly this pandemic is affecting the economy. And the news is quite grim. On Thursday, Statistics Canada released its March job report, announcing that more than 1 million jobs have already been lost. The official jobless rate is now 7.8 percent, a sharp rise from 5.6 percent in February. What this will mean for policymaking remains to be seen, but MaRS Data Catalyst group is already in on the conversation with the subsequent release of their report on the March figures, Economic Impacts of COVID-19.

“We’re trying to tell more data stories and to make data more accessible,” says economist and Data Catalyst’s lead executive Matthias Oschinski. The group is a small-but-mighty collection of statisticians, data analysts, computer coders and economists who work with government agencies, corporations and academics to use data-driven insights to help decision makers. They digest complicated, raw information and produce research and reports that are visual, easily understandable and interactive.

We asked Oschinski to break down some of the charts from their latest report and what they mean for the Canadian bottom line.

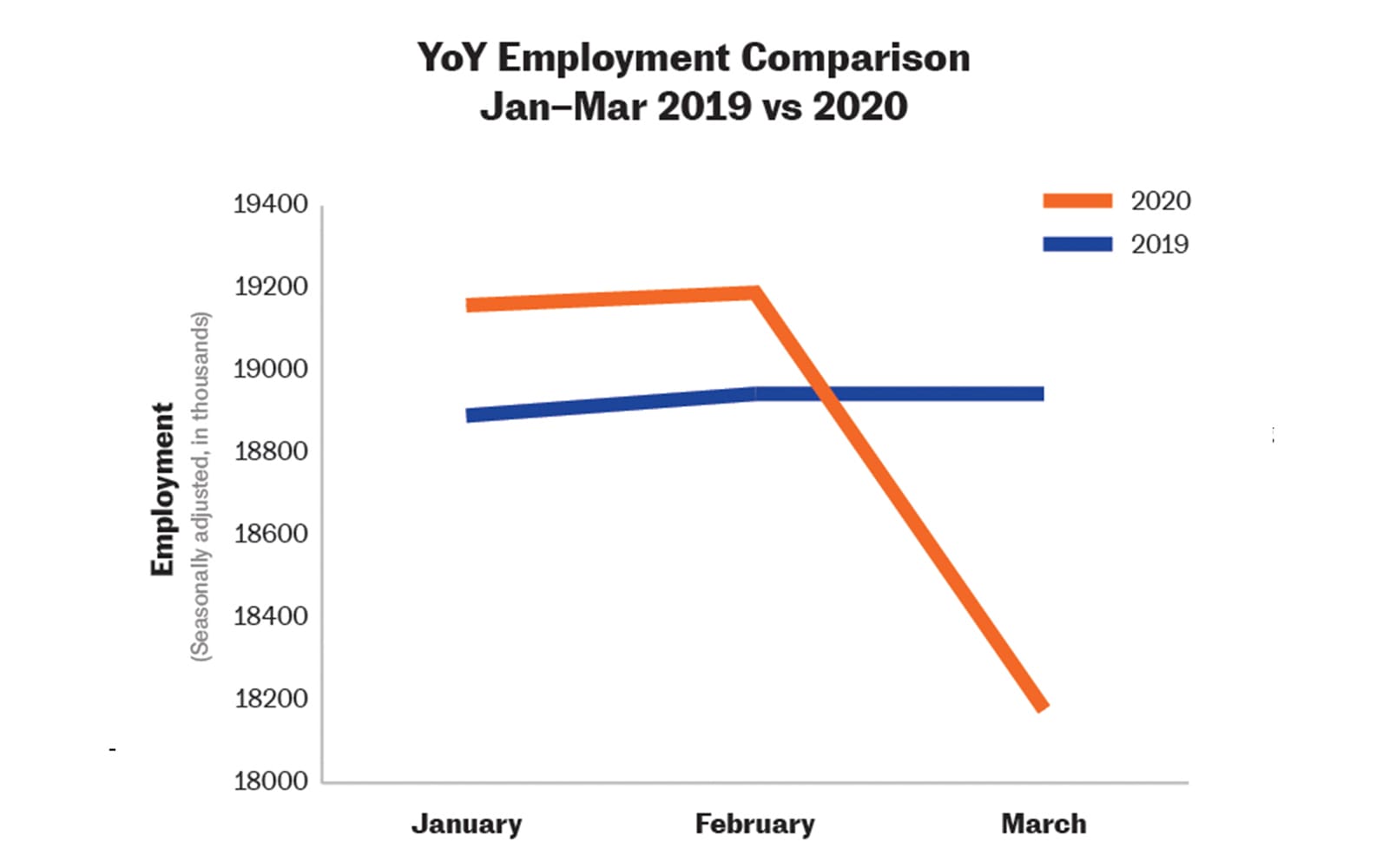

The drop in jobs has been sudden and steep

It’s hard to argue with the numbers here. Last March job losses tallied just 200 people, practically a drop in the bucket. This year? One million, which is less of a bucket and more of a tsunami.

“What stands out is it’s so early on in the crisis, and it’s already steep,” says Oschinski, pointing out that when COVID started impacting the U.S, forecasters there said Americans might experience up to three million lost jobs by the summer. It’s only April and they’re already at six million.

“The predictions about how deep this would go are already moot,” he says. “About two weeks ago, I was on a Zoom call with some colleagues who aren’t economists, and they asked me why I looked so depressed. I could already see what’s coming.”

While the entire country is experiencing record job losses, the hardest-hit provinces so far are ones that have a vibrant tourism and retail sectors, like Ontario, B.C and Quebec, and places like Alberta, who is suffering fallout from the crash in oil prices. Oschinski says the ripple effect of all those people not spending money will trigger even more job losses, which will likely deepen any recession.

Recovery could take longer than expected

Oschinski says the thing that worries him most is that the sudden drop in employment rates that Canada is experiencing now is already as big as the dip the country had during the recession of the early ’90s, and even larger than the one emerged after the 2008 crash.

“This hints that it’s just the beginning,” he says. “There was hope a couple of weeks ago that we would get a V-shaped recovery — a sharp drop in employment figures, but then a very speedy recovery.”

This is what happened in 2008, where, in Canada at least, the truly serious financial pain only lasted about seven months. But now economists fear it will look more like a U — which is a prolonged period of unemployment for many people and a slower recovery, especially because of the ongoing uncertainty about when there will be a vaccine that would make returning to business-as-usual a plausible option.

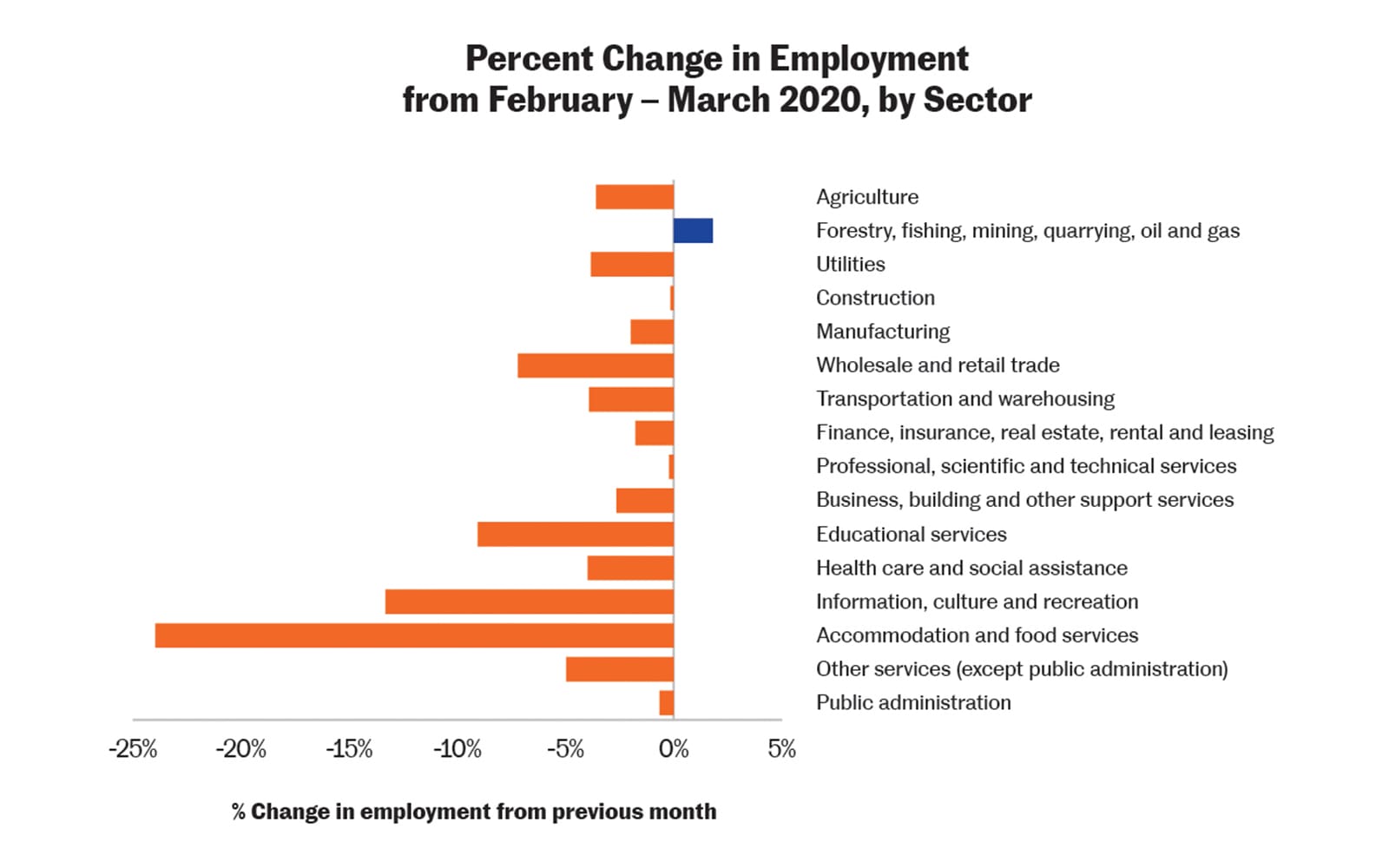

Some sectors may have trouble bouncing back

“These charts aren’t surprising,” says Oschinski about job losses in sectors like accommodation, food, retail and culture (which includes things like live performances). “These are industries where you have a lot of human interaction and where remote work is less of an option. But what is surprising is the strength of the dip.”

March saw a cliff-worthy 24 percent drop in employment in Accommodation and Food Services, a 9 percent decrease in employment in Education Services, a 13 percent drop reduction of jobs in Information, culture and recreation and a 7 percent decrease in employment in wholesale and retail trade. Of course, there’s the immediate economic effect of so many people being out of work for the foreseeable future, but Oschinski says a longer-term concern is that even when some of these industries start to recover, employers may have automated their jobs out of existence. Education and retail, for example, are rushing to move their industries online.

“This crisis could be an accelerator of increased digital services,” he says. “Employers will have been thinking about how they can automate more so they’re less likely of being hit if there’s another pandemic. This could mean you need fewer employees.”

Leah Rumack

Leah Rumack