Drug Discovery 3.0: The traditional research model is being turned on its head

Corporate players are collaborating with startups and partnering with academic institutions

At JLABS in Toronto, the startups are moving in.

On the 13th floor of the West Tower of MaRS — an innovation hub in downtown Toronto — chemists, biologists, software engineers and immunologists are settling into the 40,000-square-foot incubator that will be their new home base.

JLABS will eventually house up to 50 companies, and the first 24 setting up now come from diverse areas — Avrobio is developing gene therapies targeting cancer and rare diseases; SYNG Pharmaceuticals is working on a blood test for endometriosis; Neutun is developing a seizure-tracking tool for people with epilepsy; KalGene Pharmaceuticals is working on a therapeutic for people with Alzheimer’s to bring back their memories. But these startups all have one thing in common: each is working on how to turn promising science into products that will improve the health and well-being of patients in Ontario and beyond.

JLABS is the brainchild of Johnson & Johnson Innovation, a branch of 130-year-old multinational Johnson & Johnson (J&J), a company with global sales of $74.3-billion (U.S.). The MaRS site is JLABS’ sixth — the others are located in San Francisco, San Diego, Houston and Cambridge, Mass. — but it’s the first one outside of the U.S.

Today JLABS Toronto’s new inhabitants are busy setting up their new office and lab space, supplied with leading-edge, state-of-the-art equipment. Some gather in clusters in JLABS’ expansive common area. Here, comfortable purple couches and warm-toned wood tables are surrounded by floor-to-ceiling windows and a killer view of University Avenue’s “hospital row,” the University of Toronto campus and the stately Ontario Legislative Building.

“We want to create a space where people come and talk, where different sectors are talking together,” says Rebecca Yu, head of JLABS Toronto.

Yet for everything these promising startups get, J&J isn’t asking for any equity in return.

“We don’t own any intellectual property, we don’t have first rights, we do not seek confidential info,” says Ms. Yu. “The company doesn’t have to sign with us.”

It’s an intriguing example of how the traditional model of drug discovery is being turned on its head, as corporate players become more open to outsourcing, engaging earlier in the innovation cycle, collaborating with early-stage startups and partnering with academic institutions.

Drug manufacturers have been increasingly shrinking away from in-house research because while major internal spending can sometimes lead to a blockbuster drug and billions in worldwide sales, companies can also invest hundreds of millions into developing drugs that ultimately prove ineffective, unsafe and unmarketable. Outsourcing R&D to startups and smaller companies, and working with open source labs, filters out the early mistakes, enabling corporations to make their big investments in the clinical trial and commercialization stages.

The new outsourcing model is good news for Toronto, which is poised to be a super hub in health. With its wealth of world-leading academics and researchers, Toronto has traditionally been a leader in discovery, but less successful when it comes to commercialization. With the rise of urban innovation hubs, however, this trend is starting to reverse because a new model of open innovation has taken shape, drawing together disparate partners in the discovery cycle.

MaRS is an example of this model, housing pre-competitive labs, entrepreneurs and pharma companies under one roof.

“JLABS is a strategy based on the premise that great science and technology is just as likely to come from outside the walls of a big company like Johnson & Johnson as inside,” says Melinda Richter, head of Johnson & Johnson Innovation. She’s in charge of all six JLABS incubators and is based at the flagship location in San Diego.

Science scouts

Finances can be a huge obstacle for startups in the life sciences.

“There is so much great science and technology that gets left on the shelf, not because it isn’t good but because they hit these obstacles that make it impossible to go forward,” says Ms. Richter. “We want to make sure they have everything they need, so that if it fails, it fails for the science, not for other reasons.”

While Johnson & Johnson does hope that deals will come out of the incubator — Ms. Richter says the company has specialized “science scouts” that interact with the startups and recommend deals to help the most promising progress further — it is fine with giving its startups the freedom to choose.

Jinzi Zheng is the co-founder of Nanovista, Inc., one of the local startups that has moved into JLABS Toronto. The company develops visualization agents designed to enhance high-precision cancer therapies like surgery and radiotherapy.

Nanovista won a year of free residency through JLABS’ “Quick Fire Challenge” competition, and Ms. Zheng says they jumped at the opportunity because they believe in strategic partnerships.

“I knew that JLABS was more than just a pretty space and shiny new equipment. To us, being at JLABS means that we can leverage J&J’s network and tap into their expertise both from a commercialization side and from a product development side,” says Ms. Zheng.

Partnering to bring cancer drugs to market

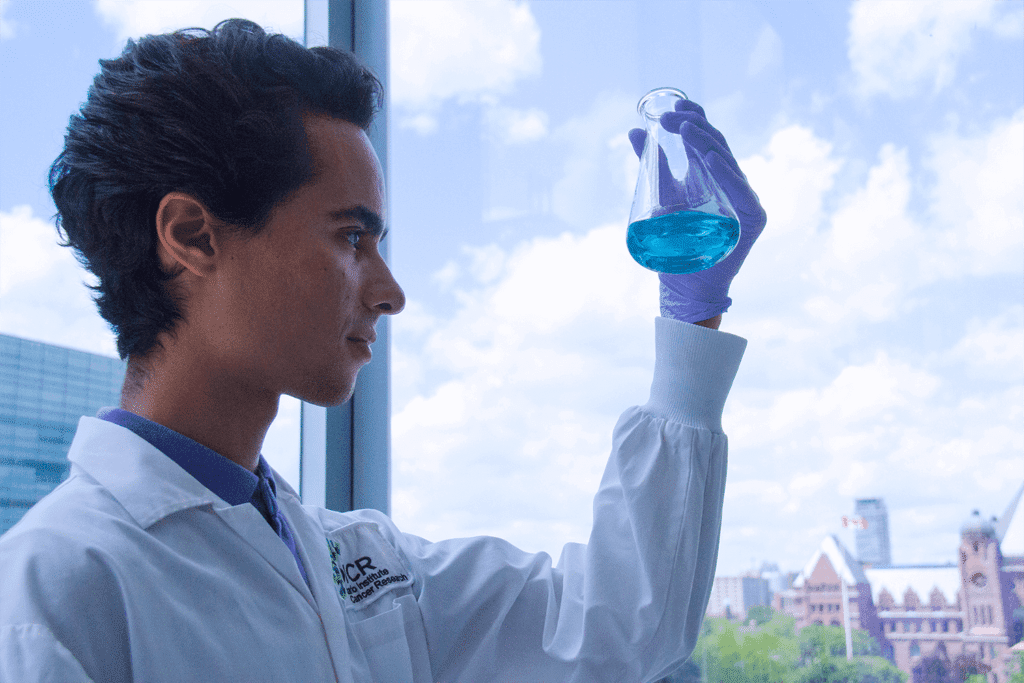

At the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR), located in both the South and West Towers of MaRS, analytical chemist Ahmed Aman is using a mass spectrometer to determine the presence of a test compound in a sample. Like everyone else at the OICR Drug Discovery lab, Mr. Aman is working on developing compounds that will hopefully become significant new cancer drugs, but he has to analyze the physical properties of the com- pound first.

“It’s looking at how our drugs permeate the system and whether they actually stay around long enough to do what they are supposed to do,” explains David Uehling, group leader of medicinal chemistry at OICR.

Across the room, Richard Marcellus, principal research scientist in the biology group, is using a Biacore T200. This state-of-the-art instrument, which looks a bit like a photocopier connected by tubes to two beakers, provides a highly effective way to see how well a compound binds to a protein.

The Drug Discovery lab is one of the hotspots of discovery at OICR, a not-for-profit organization focused on the prevention, early detection, diagnosis and treatment of cancer. It’s a place where the spirit of scientific inquiry meets the drive to see drugs get to market.

Christine Williams, deputy director and vice-president of outreach for OICR, says the program’s mandate is translational research — taking the great discoveries made in basic science and biology and moving all that understanding and investment into clinical practice where it will impact patients.

Jeff Courtney is chief commercial officer at Fight Against Cancer Innovation Trust (FACIT), an independent business trust established by OICR to propel commercialization activities. “Our process is trying to take the work that’s coming out of OICR and marry that to partners, usually pharmaceutical or large biotech companies,” he says. FACIT also provides seed capital if necessary.

Sometimes the technology is innovative enough that they can go straight to a partnership. Mr. Courtney gives the example of a partnership with Janssen Pharmaceuticals, which is part of Johnson & Johnson, to develop a set of novel therapeutic compounds to treat haematological (blood) cancers. The deal includes an option to license the drug, worth about $450-million, which would then be cycled back into research at OICR.

“It was a beautiful example of taking an early idea from academia, working collaboratively with the researcher and OICR, and taking it to a point of partnership,” he says.

![]()

This article appears in our special report on Urban Innovation, which highlights how downtown density is driving the new economy. This report examines all the elements that fuel innovation at MaRS, showing how our building and location, corporate and academic partners, and the tenants and the startups in our network all contribute to getting high-impact solutions to market faster, both in Canada and beyond.

Shelley White

Shelley White