We are drowning in plastic waste

Can technology save us?

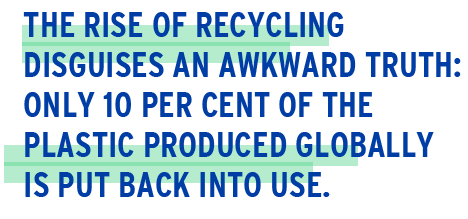

In the three decades since Canada pioneered blue box recycling, similar systems have become familiar sights in cities throughout the developed world. But the rise of recycling disguises an awkward truth: only 10 per cent of the plastic produced globally is put back into use. Even in a rich nation like Canada, where all but the most isolated communities can recycle, plastics are recovered at a much lower rate than materials like paper and metal.

Now technology is rising to meet the challenge posed by the enormous heap of plastic discarded into the environment every year, as well as materials that are collected but end up in landfill because they can’t be recycled economically.

![]()

Fish swimming through oceans of plastic

How big a predicament is plastic? Scientists estimate that up to 12 million metric tons of plastic is swept into oceans every year, a problem highlighted by the recent discovery of two vast garbage patches in the once-pristine Arctic Ocean to go along with those already polluting the Pacific.

The recycling of plastic is improving so slowly in part “because there isn’t an easy rule for people to follow,” says Ashley Wallis, a program manager with Environmental Defence, a Canadian non-profit agency.

One problem is that so many varieties of plastic are in use; another is the fact that municipalities have different rules. For example, Toronto residents can recycle white plastic forks but not black ones, while in neighbouring Mississauga, both types go in the trash because they’re too small for that city’s sorting machinery.

![]()

Recycling can be like a spiral of declining value

Recycling programs are picky because not all plastics can be treated the same. While some, such as water bottles made of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, are relatively easy to recycle, others, such as ketchup bottles, contain multiple layers of plastic that are much more difficult to process.

In many cases, instead of material fit for new products, recyclers end up with a gloop containing contaminants that affect its colour, clarity and other physical properties. Cleanliness can also be an issue. For example, very few Ziploc bags are recycled. Those that are — just 0.2 per cent — are collected via grocery-store drop-off boxes because those found in curbside bins are generally too dirty to make a valuable product.

So, for many plastics, recycling is more like a spiral of declining value. The complexity, combined with high costs for collecting, transporting and sorting, would seem to create little incentive for investment.

![]()

The key to recycling more plastic? Upcycling

Yet new technology may soon fill the gap by launching a wave of “upcycling” that takes plastics now considered hard to recycle economically and turns them into something much more valuable.

GreenMantra Technologies, based in Brantford, Ont., is perfecting a process that breaks down waste plastics — including hard-to-recycle grocery bags and plastic film — into small molecules. Instead of being reassembled as they were, the components become entirely new products, such as waxes and lubricants, that are up to five times more valuable.

GreenMantra already produces about 5,000 tonnes a year of ingredients used in coatings, roofing shingles and adhesives for packaging. It has also worked with the City of Vancouver to create an asphalt surface for roads that incorporates its waxes.

But the company has even bigger plans, says chief executive officer Kousay Said. “Now that we have successfully commercialized the wax platform, we are moving into polystyrene,” which he says is not currently recycled “at any significant rate.”

![]()

Recycling more plastics on-site

Whereas GreenMantra buys waste plastic that has already been sorted and turned into pellets, another Canadian company is working to recycle mixed plastics wherever they are.

Pyrowave has created a portable system that can be installed anywhere there is a lot of plastic waste — from auto-assembly plants to grocery stores and plastic sorting facilities. The device works like a reverse vending machine, using microwave technology to break down plastics placed in it, and then creating waxes, oils and monomers, which are small molecules that can be turned into new products.

Then, once it has collected and sold the output to manufacturers, Pyrowave shares the proceeds with the clients that rent its machines, creating an added incentive to recycle.

Jocelyn Doucet, chief executive of the company, which has offices in Montreal and Oakville, says the market is hungry for solutions that derive value from waste, especially if they are convenient: “Our tech is very robust, it can take very contaminated plastic material, mixed plastic material, it doesn’t matter — you’ll get the output.”

![]()

But upcycling isn’t the answer to all plastic woes

Upcycling shows great promise, says Joe Hruska, vice-president of sustainability with the Canadian Plastics Industry Association (and one of those responsible for creating the blue box program in Ontario), but it’s no magic bullet.

He feels the best results come from an approach that emphasizes responsible consumption and the reuse of plastic, as well as recovering it from the waste stream.

Still, with some skeptics suggesting there will be more plastic in the oceans than fish within 30 years, alchemists who can turn it into something worthwhile are bound to give recycling a healthy boost.

![]()

Feeding the imagination with waste plastic

Startup ReDeTec keeps 3D printers humming with recycled plastic

3D printing is revolutionizing the way some professionals work, enabling designers and architects to create prototypes and working models much more rapidly than in the past. The downside: It can be incredibly wasteful. Not only do 3D printers use an excess of plastic during production, even the final product often ends up in the trash.

The plastic lament used in 3D printing costs more than $30 a roll, so Toronto-based startup ReDeTec sees a substantial upside in the recycling market. It has created a compact desktop device called the ProtoCycler, which grinds up waste plastic, and melts it, before extruding it as a lament ready for reuse.

So far, the ProtoCycler can handle only PLA and ABS, the two most common types of printer plastic. But new printers coming on the market can use PET, the plastic commonly used in water containers, so ReDeTec is now researching ways to adapt its technology.

This raises the possibility that soon even your old water bottle could be converted into futuristic prototypes that could change the world.

![]()

David Paterson

David Paterson