Vital signs: Canada’s health tech sector is at a critical juncture

Funding is down, the market is in turmoil and supply chains have new snarls. And yet, despite the many challenges, there are significant opportunities in the life sciences sector. Here, a snapshot of the shifting investment landscape and promising areas of innovation.

This report provides a broad overview of the major trends happening in Canada’s life sciences ecosystem.

Seizing the moment

The oft-repeated truism about innovation in this country — we excel at research, underperform at commercialization — remains unfortunately true in the Canadian health technology sector. But the current geopolitical moment, with its intensifying tensions, has made things even more challenging. Our market has always been significantly smaller than the United States, and startups in biotech, medical devices and digital health have necessarily looked to the U.S. for investment, manufacturing capability and customers. Now, with capricious American trade policy and market turmoil, those startups are grappling with new tariff implications (earlier this summer, Trump was threatening 200 percent tariffs on pharmaceuticals) along with supply chain snarls and onerous investor demands.

The sector faced headwinds long before Donald Trump returned to the White House, however. Too many promising innovations get stalled trying to make it out of the lab.

- Our regulatory landscape is complicated and fragmented.

- There’s a persistent lack of sufficient early-stage funding.

- Across biotech, medical devices and digital health, capital is increasingly flowing to late-stage mega deals.

Knock-on effects

The lack of early funding can have a serious impact on the pipeline of ventures. These companies have emerged from our academic institutions and have been supported along their — often very long — journey from academia to building out their businesses. “If we lose this cohort of companies, we’re really going to feel it in five to 10 years,” says Louise Pichette, director of health sciences at MaRS. “We can’t just create a wave of commercial-stage companies from scratch.” Without support, we risk stalling our growth, weakening our competitiveness and missing out on the very innovations we helped develop.

If the political situation has amplified the struggles of the industry, however, it has also given rise to other, more encouraging, trends. Thanks to recent cuts at the National Institutes of Health and other American research organizations, the cancellation of international student visas, and relentless political pressure on colleges and universities, we’re seeing the slow reversal of the brain drain that has long plagued Canada. In a recent poll of 1,200 U.S.-based scientists conducted by Nature, 75 percent said they were considering moving, with Europe and Canada their top destinations. According to recruiters, hundreds of American doctors, approximately double the number last year, have reached out about relocation. Capitalizing on this incipient exodus, University Health Network launched the ambitious Canada Leads 100 Challenge in April to recruit 100 world-leading early-career scientists to Ontario. UHN hopes to stimulate similar activity across Canada, eventually bringing a thousand such scientists to the country.

“We are in a very important moment of time, given the current geopolitical situation. How can we seize it?”

A renewed sense of national unity and an acute focus on sovereignty in every area of Canadian life can also benefit health tech. Startups that just a year ago might have eagerly relocated to the U.S. are now choosing to stay and build here. Canadian investors, some of whom may have been slower to fund local ventures, are expressing all-new interest in homegrown companies. While the size of our market remains an obstacle to scale, the dismantling of interprovincial trade barriers, a process now underway, is also a crucial step in expanding and diversifying that market. Katie Hayes, a MaRS advisor, believes that, thanks to good non-dilutive funding, grants and a supportive local ecosystem, a lot of companies can go far without leaving Canada — at least to the point where they don’t need funding from the U.S. “There’s a path to doing that,” she says. “And I think folks are celebrating that.”

“Most of us in the public domain take science and medicine for granted. You’re sick; you get medicine, you go to the hospital. We rarely ask: Where did this medicine come from? How did this happen? Look at what’s happening now — the NIH is being crushed in the United States. People are not marching in the streets. I don’t think the public fully realizes how fantastic our existing infrastructure and healthcare system and scientific enterprise is until it gets really broken, and then they say, ‘What’s going on?’ So I think we all have a responsibility to do a much better job outside our scientific ecosystem to engage with the public and to remind people that the medicine that we take for granted across society doesn’t just happen — it needs investment.”

It’s a cliché of the tech sector that Canadians are averse to risk. But the volatility south of the border is making that aversion seem, in some ways, reasonable. If health tech can capitalize on this historic moment, it could go a long way to remedying many of the sector’s most persistent problems. “Challenging economic times breed really resilient companies,” Pichette says.

Early-stage investment in 2024 saw a dramatic drop across the life sciences.

Uncertain territory

Health tech entrepreneurs are navigating a shifting funding landscape.

The entire health tech sector has seen a pull-back in funding. According to a report by Pender Ventures, compared to 2023, venture funding in 2024 dropped 18 percent, ending at $700 million across 287 deals. MaRS analysis shows that early-stage investments were hit hardest, with funding amounts down 30 percent and deal counts down 26 percent. Biotech, in particular, faced significant headwinds, as did digital health startups. Medical devices saw a modest increase in funding, compared to 2023, though this was driven, for the most part, by a few large deals.

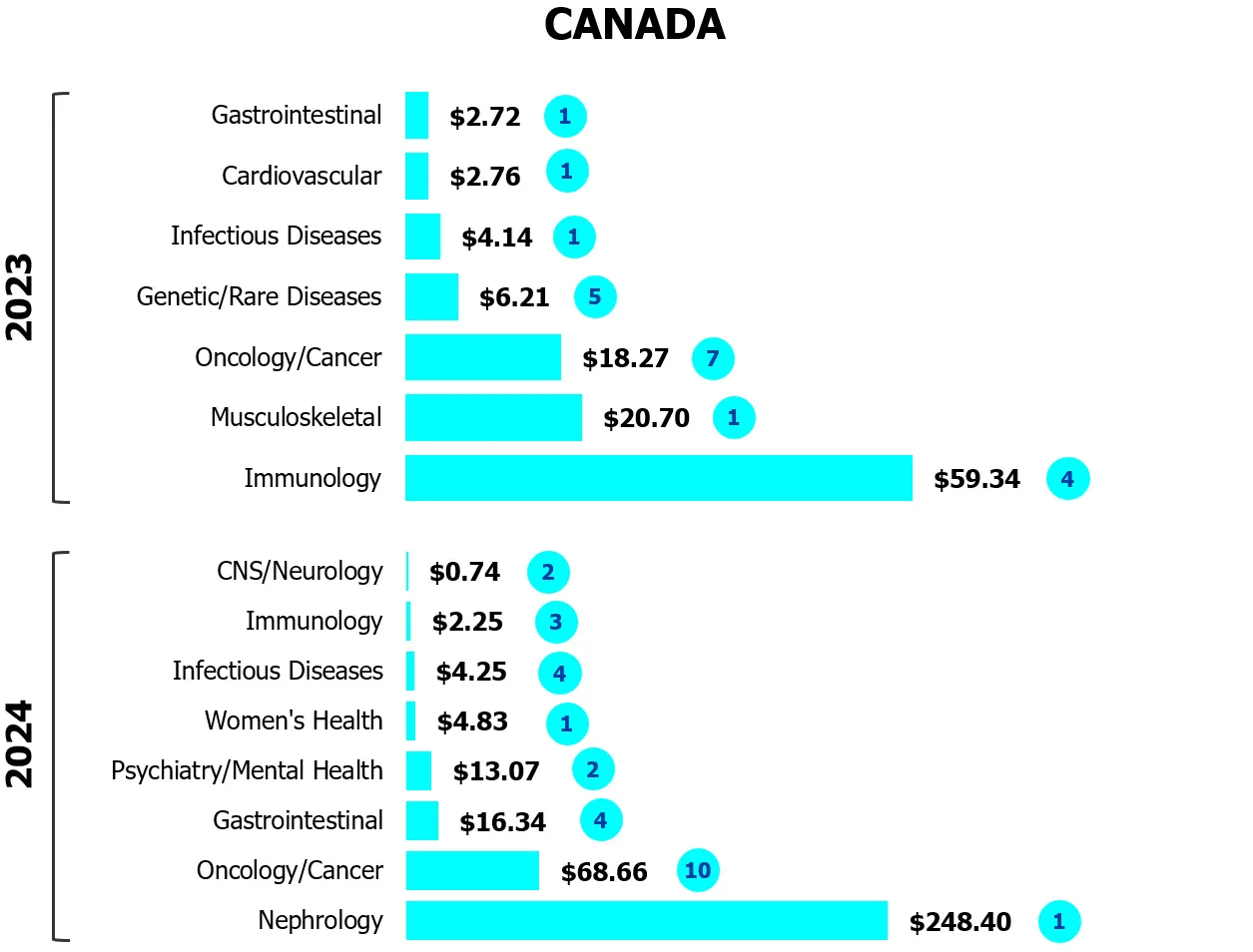

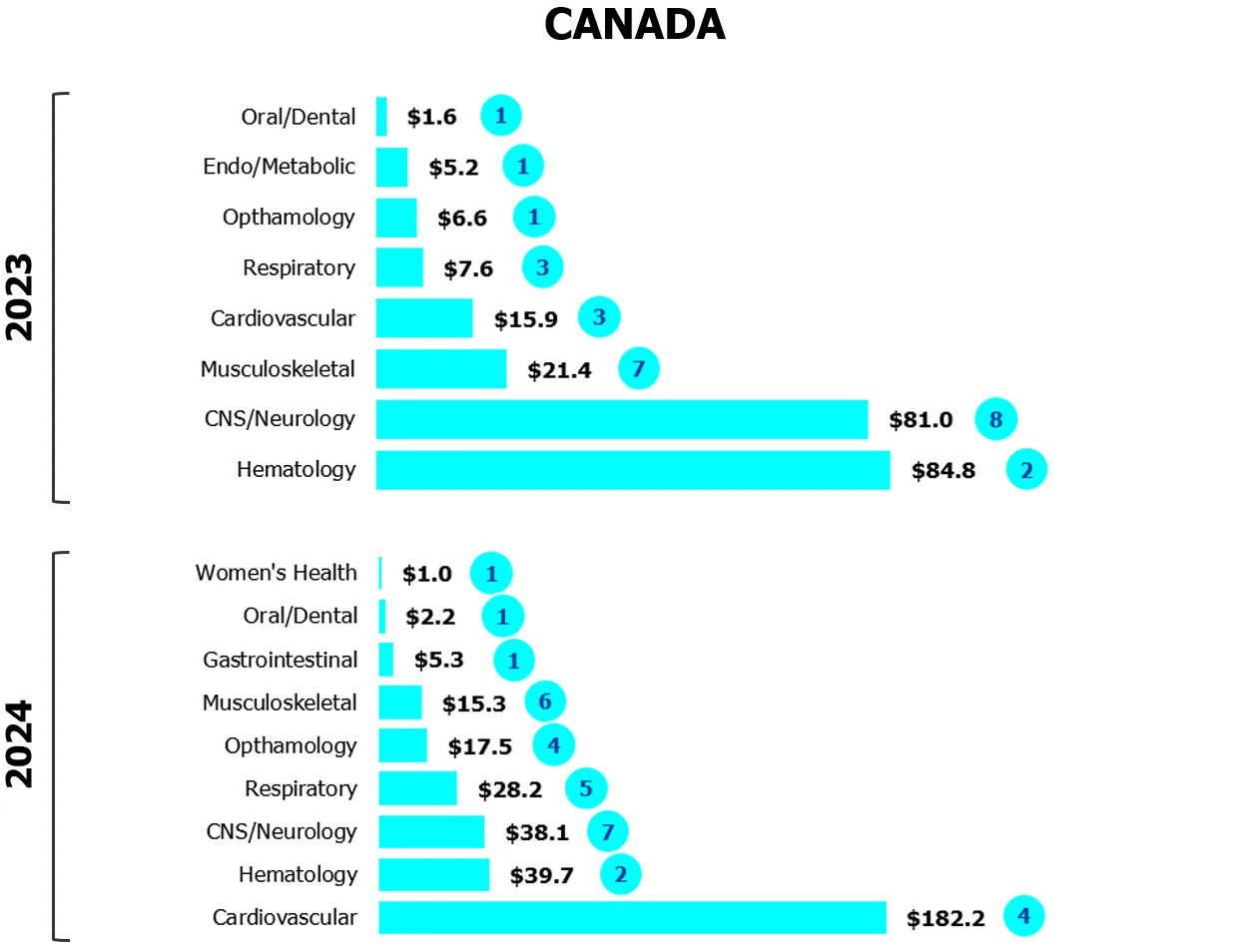

Biotech: The year of the mega-deal

In 2024, many investors shied away from riskier science, with its significant R&D costs and long journey to commercialization. There was a marked decline in interest in genetic medicines given their relatively small patient populations, high technological and manufacturing risk, and limited commercial returns. What funding there is, is flowing primarily to mega deals where ventures already have deep connections with international investors. Last year, the lion’s share of investment — 22 percent of all health sciences funding in Canada — went to Borealis Biosciences’s $248-million Series A round.

Figure 1

Investors gravitate to safe bets

Capital invested across biotech-pharma by indication

($M CAD/number of deals)

Source: MaRS analysis of Pitchbook data

Similar funding trends are present in the U.S. as well. South of the border, there has been:

- Reduced investment in cell and gene therapies, CRISPR and regenerative medicine but increased investment in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) as well as immunology and inflammation (I&I).

- Sustained growth and continued interest in the oncology and immunology space, partly due to prevalence (continuing to rise 12 percent a year) as well as investors choosing less-risky disease areas with active pharma interest.

- Pullback by some drugmakers, including Pfizer, which recently stopped selling its gene therapy for hemophilia.

Biotech by the numbers

Sources: RBC, OECD, MaRS analysis

“There’s a lot of capital efficiency here: Canadian companies are very careful and thoughtful around how they deploy capital.”

Grey Matter Neurosciences secured $14 million in seed funding.

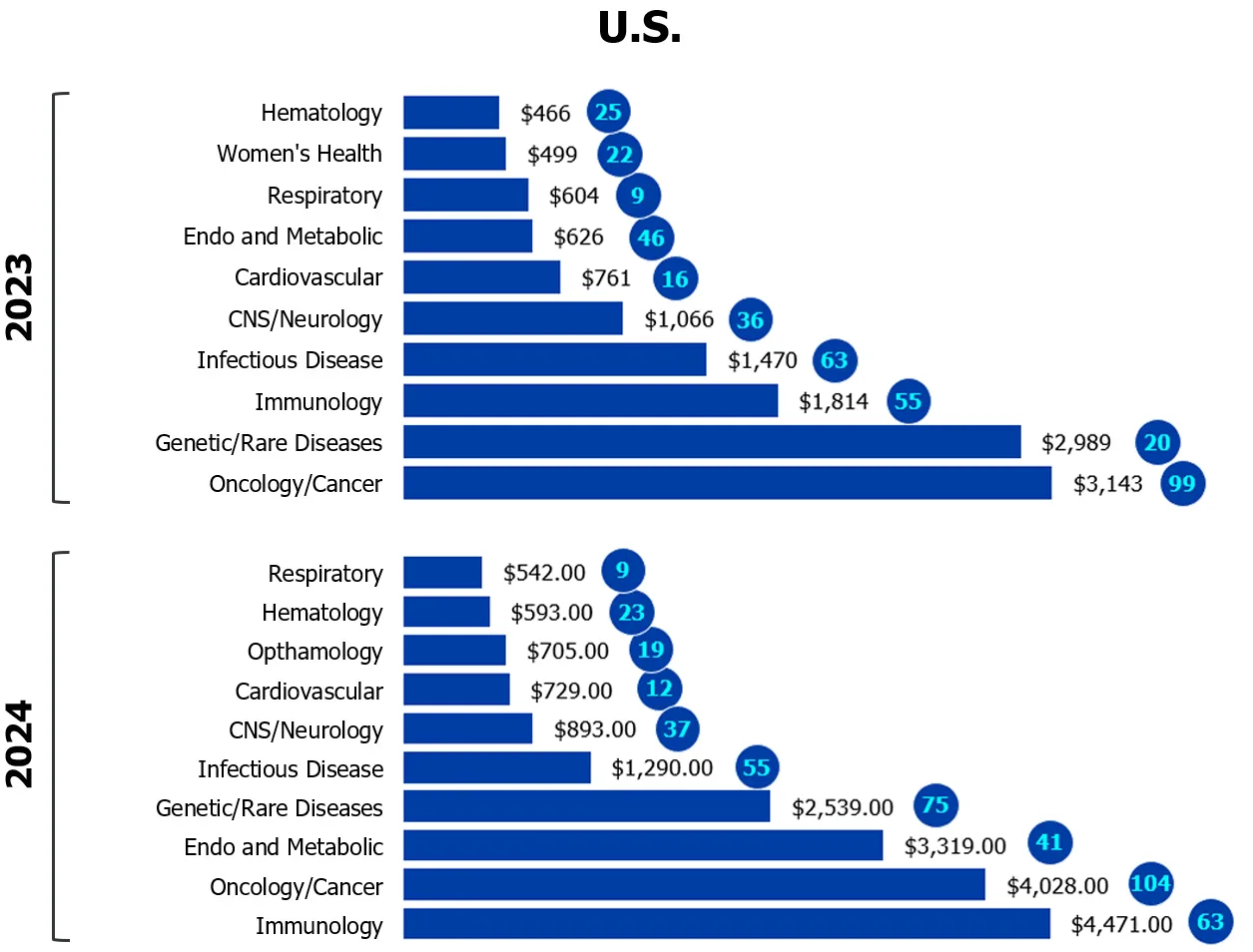

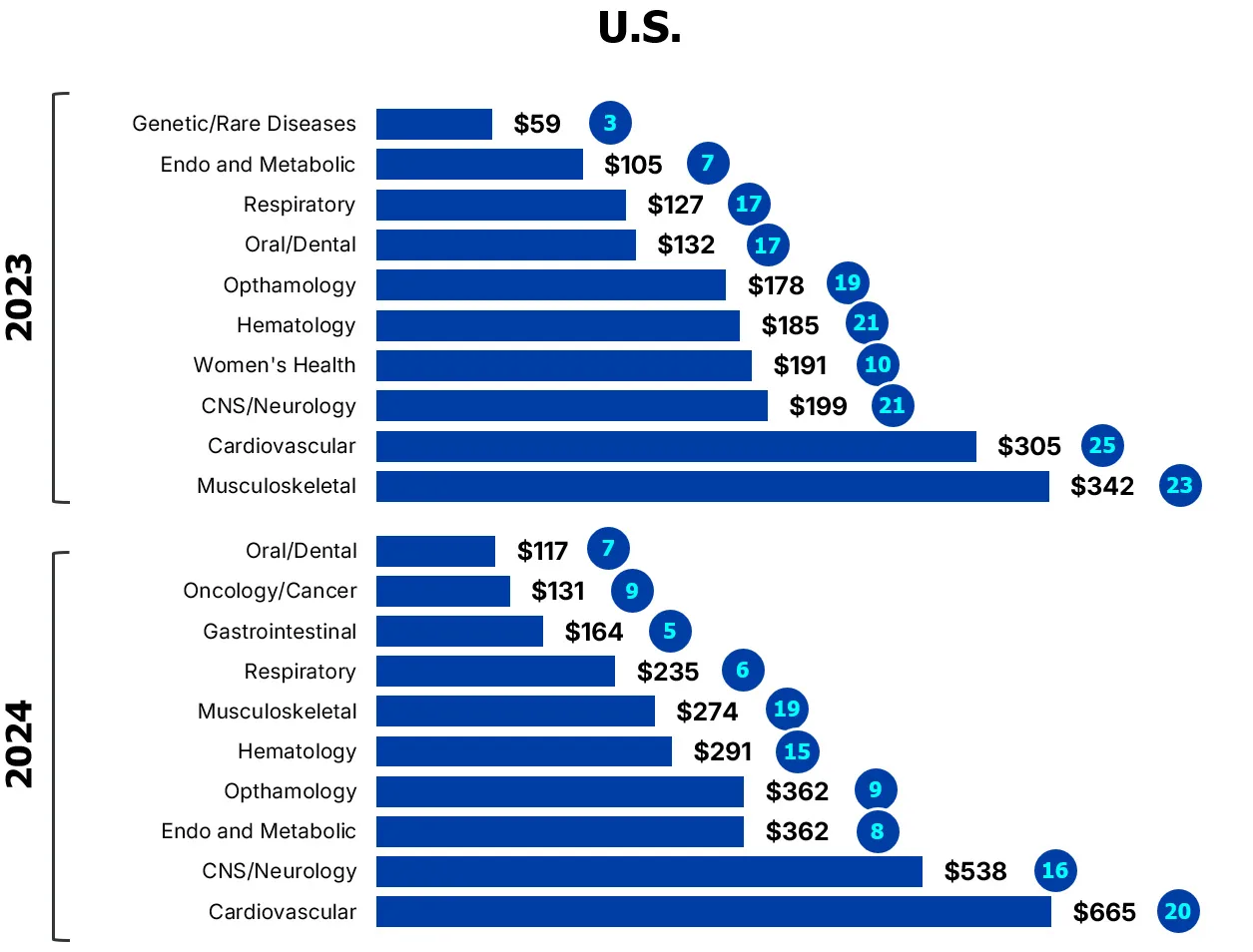

Medical devices: Facing new headwinds

Medical device ventures saw a 30-percent funding increase in 2024 (compared to 2023), thanks to a few large deals. For instance, Stethophone’s $18-million seed round and Kardium’s $143-million late-stage round accounted for 86 percent of all cardiovascular funding, while RetiSpec and Grey Matter Neurosciences contributed their combined funding of $32 million to the neurology pool.

Startups in this sector are having a particularly challenging time in 2025 because of potential tariff threats, supply chain challenges and economic uncertainty. Companies who manufacture internationally or rely on parts from other countries are especially struggling. As with biotech, more capital is being allocated to later-stage, de-risked deals. But new opportunities are emerging, along with some cautious optimism, due to national policy shifts (“Buy Canadian”), market diversification and discussion around the removal of inter-provincial trade barriers. In September 2025, the Ontario government announced the launch of the Health Innovation Pathway, which aims to speed up the process of reviewing and adopting medical devices and procedures, testings, digital tools and medical imaging. With a focus on supporting Ontario-based innovations and ensuring local patient care, this type of initiative could help bolster the ecosystem.

Figure 2

Strong showing for later-stage deals

Investor bets on cardiovascular devices gained traction in Canada and the U.S. in 2024

($M CAD/number of deals)

Source: MaRS analysis of Pitchbook data

Rishi Nayyar, CEO of PocketHealth, landed a $45-million Series B raise.

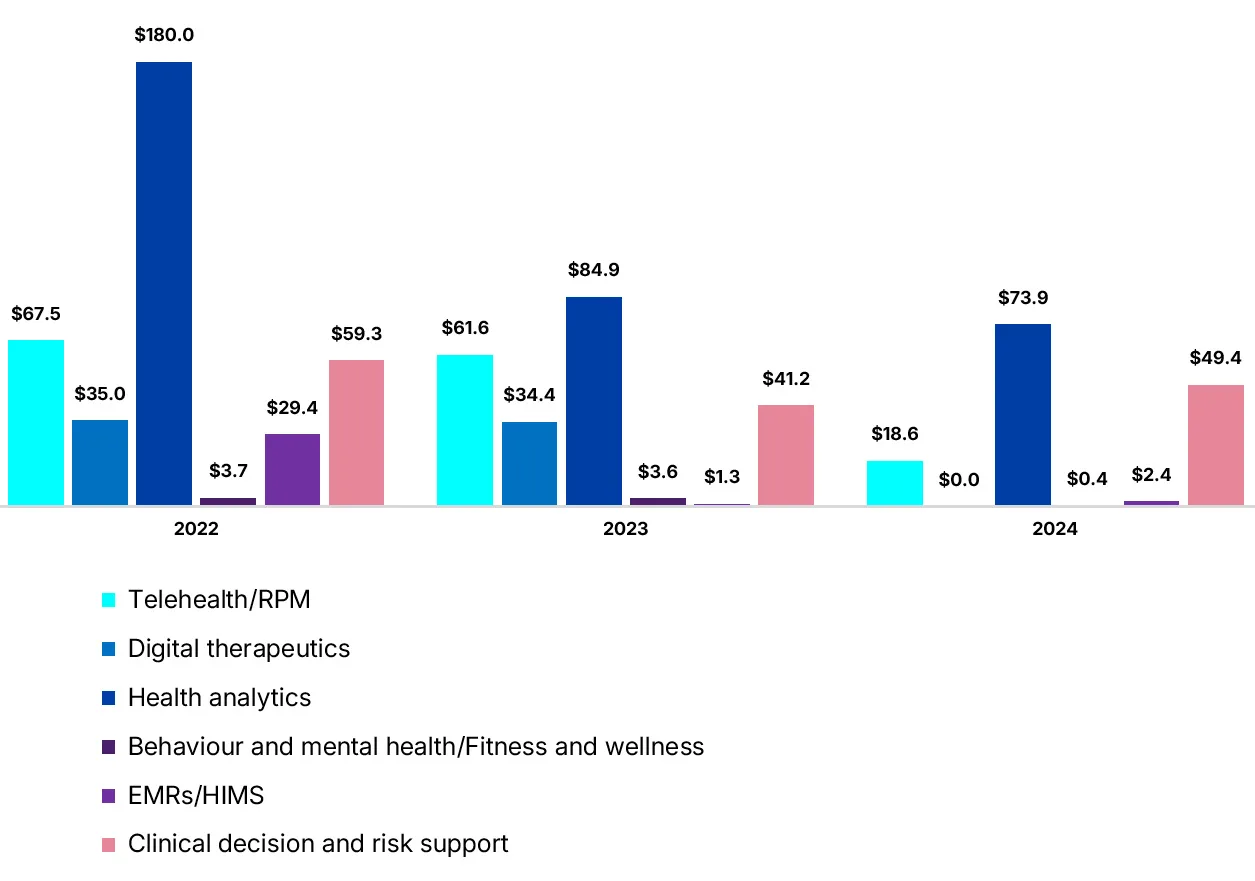

Digital health: Shifting priorities

MaRS analysis shows a 36-percent decrease in funding for Canadian digital health ventures in 2024, compared to 2023. The pullback was in telehealth and remote patient monitoring, with some growth in behavioural/mental health and fitness/wellness. The electronic medical record segment decreased slightly, but was driven by PocketHealth’s $45-million Series B raise, Wisedocs’ $12.7-million Series A and Clinia’s $10-million Series A.

Practitioners continue to embrace validated platforms that optimize workflow, with AI scribes seeing significant uptake from primary care clinicians. At a recent Ontario Medical Association trial, which offered physicians access to AI scribe products, more than a thousand GPs signed up for 150 test spots. The federal government has also recognized the value of leveraging AI to reduce healthcare provider burdens; last year, it invested $15.3 million in Health Compass II, an AI integration project from a consortium of Canadian health tech companies.

Figure 3

AI captivates investors

Gradual pullback in digital health investment

($M CAD)

Source: MaRS analysis of Pitchbook data

Strategic plays

New approaches aim to bridge funding gaps.

As venture capital pulls back, new players, partnerships and models are emerging. Here are four promising developments.

1. Philanthropy steps in

With depth and continuity of capital a constant hurdle, not to mention securing domestic sources of funding, startups are looking increasingly at philanthropic organizations.

Early this year, the Weston family launched the Wittington Innovation Fund to support environmental and health tech startups; it led a $14-million round by Grey Matter Neurosciences, which is developing a focused ultrasound treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease. Catalytic capital models, which have been used to commercialize Type 1 diabetes and cystic fibrosis therapies in the U.S., are particularly promising.

This past April, Lumira Ventures and the Terry Fox Foundation partnered to launch the Cancer Breakthrough Fund, which will invest in companies focused on delivering novel therapies to patients fighting cancer. This is the first collaboration of its kind in Canada, and is designed to help close the gap for donors who want to invest in diagnostics and therapeutics diagnostics and therapeutics further along in development.

The SickKids Breakthrough Fund is a similar philanthropic venture, and allows investors to help fund the commercialization of child health innovations, from diagnostic tools to precision therapies. “These catalytic capital models are creative,” says MaRS’s Louise Pichette. “If you want to donate to something with forward momentum, a cause that’s important to you, supporting a venture is quite compelling.”

“Although VC provides a meaningful avenue to access funding, it does come with pressure to provide an exit in an acceptable time frame. Everyday Canadians, family offices and angels are not rigidly beholden to the timeline of a fund. They provide the best source of capital to create longstanding businesses that remain Canadian, own their IP and generate global revenue.”

2. Founder-first models

Recognizing that intellectual property from academia alone can be insufficient, investors are also supporting experienced serial entrepreneurs outside academic institutions. This model can work well, with experienced founders able to bring learnings from earlier ventures to their next startup.

Steve Tregay, who is managing partner at Mission BioCapital, argues that entrepreneurs who have founded multiple startups can really accelerate innovation. “Density really does matter,” he says. “Once you get that density — people getting comfortable with entrepreneurship, where they can build their companies efficiently — it’s a really great way to drive innovation at a faster pace.” A number of Canadian biotech companies were built this way: Congruence Therapeutics, Ripple Therapeutics, Innospera Pharma, Borealis Biosciences, Innospera Pharma and Providence Therapeutics.

There are challenges to this model, however. For one, a lack of academic affiliation can limit non-dilutive funding options. Also, a venture’s success could hinge more on the founder’s ability to raise capital through their network; no matter how compelling their technology, a founder’s background and expertise may lead investors to invest just as much, if not more, in the founder than the tech itself.

3. Pharma filling capital gaps

Obtaining non-dilutive dollars through pharma partnerships is becoming increasingly important to get companies through the early stages of development (in biotech, this typically requires $2- to $10-million fundraising rounds). Last November, for instance, biopharma company Sanofi made a strategic investment in Zucara Therapeutics as part of the company’s U.S.$20-million Series B financing round, with Sanofi receiving exclusive right of first negotiation.

“Finding those connections early on and getting that support and the brand and all that cachet from the partnership can be really valuable,” Pichette says. That said, changes to the FDA and uncertainty around Trump’s most-favoured-nation prescription drug pricing are making pharma groups more cautious.

4. Revisiting build-to-buy

The build-to-buy model was popular with biotech investors in the 2010s, allowing pharma companies the option to acquire a startup or its assets in return for early investment. Creative VC firms are returning to this model, but with different approaches. Versant, for instance, is using a more traditional build-and-buy, as in last year’s $150-million partnership with Novartis to launch Borealis Biosciences, while others are focusing on incubating startups within dedicated studios.

Amplitude, for instance, has created the Pre-Amp Fellowship, a biotech venture creation studio for talented Canadian academics and inventors at the beginning of their entrepreneurial journey. The Novo Nordisk Innovation Hub in Cambridge, Mass. operates its so-called “co-creation greenhouse” as part of a range of partnership models. That incubator provides young biotech companies with necessary seed funding and other support even if those partnerships don’t always result in formal, legally-binding agreements.

That kind of thinking, around bolstering local ecosystems and early-stage innovators, is shared by Jamie Stiff, managing director at Genesys Capital: “There’s tons of stuff inside the university walls right now screaming to get out. And we really have to focus on figuring out ways to get that into the wild as much as possible.”

“When we look at our returns as a firm, the best returns across all our funds come from Canadian companies. This is really a great opportunity to invest heavily in Canada and really scale the creation of, of early stage, companies and startups.”

Liquid biopsies can detect cancer long before symptoms appear.

5 trends to watch

Canadian innovators are working on solutions that could democratize access to screening, refine personalized medicine and improve care.

1. Liquid biopsies: Catching cancer early on

One of the biggest reasons cancer remains such a deadly disease is that we’re detecting it too late. Many cancers, including the deadliest like lung and colorectal, are diagnosed at a stage when they’re incurable and their treatment far more expensive. Liquid biopsies could change all that.

In a traditional biopsy, a piece of tissue or sample of cells is taken from the body and then analyzed to determine if it’s cancerous. A liquid biopsy, in contrast, uses blood, saliva or urine to detect the specific materials — DNA, RNA, proteins — that different cancers shed. The procedure is fast, minimally invasive and, crucially, can be performed by a broader range of health practitioners and without specialized medical equipment. It can also detect cancer in a patient long before symptoms appear.

Liquid biopsies have been rolled out at a few Canadian hospitals, including William Osler Health System, Mount Sinai and Moncton’s Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre. A number of local ventures are also among the companies developing different approaches to these diagnostics. Adela uses a single blood draw and machine learning to detect and analyze the DNA fragments often found in cancer cells. Kingston-based mDetect’s DNA testing can quickly monitor disease progression and treatment response in patients with metastatic breast cancer or early-stage ovarian cancer. Oxford Cancer Analytics uses advanced proteomics and tailored machine learning to detect early lung cancer. Kitchener’s Asima Health, which is focused on improving access for marginalized communities, is developing same-day tests that work across multiple cancer types. Earlier this year, the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research (OICR), acquired an Ultima sequencer, a tool that allows researchers to analyze large volumes of DNA much faster and much more cheaply to detect signs early on.

“The big conceptual shift is not looking at single genes; it’s looking at the entire genome. It becomes a platform to learn not just about cancer, but potentially about other disorders as well. It really is the future.”

All these diagnostic methods have the potential to save countless lives, but also dramatically reduce healthcare costs. “Late-stage treatment costs over three times the amount compared to early stage,” says Peter Jianrui Liu, CEO of Oxford Cancer Analytics. “So not only does late detection cost lives, it also costs a lot of money for healthcare systems.”

Significant deals in cancer screening

On the whole, cancer screening saw massive leaps in capital raised in 2024, likely due to over-representation of late-stage venture capital deals.

- $46.3 million average deal size (a whopping 207 percent increase from 2023)

- $5-million median deal size (a 47-percent increase from 2023)

- $4,119 million total capital invested (a 242-percent increase from 2023)

Non-invasive diagnostics saw a lot of interest from investors: Liquid biopsy companies in North America secured ˜$1.59 billion between 2022 and 2024. Some notable U.S. deals include:

- Delfi Diagnostics landed the largest deal, securing a U.S.$225-million Series B in 2022 and U.S.$100 million in follow-on funding in 2024.

- BillionToOne fundraised the largest total amount of capital between 2022 and 2024. After closing U.S.$125 million in Series C and another U.S.$83.5 million in a late-stage VC round in 2022, it secured U.S.$140 million in debt refinancing and closed a U.S.$130-million Series D in 2024.

- Harbinger Health had the largest single-round capital raise in all cancer diagnostics for 2023, closing a U.S.$140-million Series B round.Source: MaRS analysis of Pitchbook data

RetiSpec’s platform can detect early signs of Alzheimer’s during routine eye scans.

2. Biomarkers: Using real-world data for early diagnosis

Real-world data, including the digital exhaust produced by all our devices (web searches, social media interactions, etc.), can be crucial in improving care. Several startups are developing platforms that allow practitioners to leverage this data to identify disorders years before symptoms appear, predict the progression of disease and determine potential treatment. This is especially evident in the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Toronto startup RetiSpec, for instance, uses routine eye exams to identify early signs of Alzheimer’s. Using a high-resolution image of the retina, analyzed by proprietary AI, the company looks for a build-up of amyloid plaques — a hallmark of Alzheimer’s — which are detectable in the eye years before other symptoms appear. “The eye is a central access point to the nervous system,” says RetiSpec CEO Eliav Shaked. The company partnered with select optometry clinics across North America to administer the test. This routine test could replace the invasive, expensive methods currently used to detect the pathology — lumbar punctures and CAT scans. At the moment, the company’s making its way through a regulatory study and filings that would enable them to roll out the technology to optometrists next year.

Another Toronto firm, Interaxon, has provided Muse, its EEG-powered smart headband — the same device it sells commercially to people looking to improve their meditation, sleep and overall brain health — to researchers studying various diseases. Using data from both their consumer population and research studies, it’s been able to apply AI to identify novel biomarkers for a variety of disorders and diseases, including migraine and long Covid.

Cove Neurosciences, also in Toronto, similarly analyzes brain imaging data from EEG, MRI and MEG to identify biomarkers for neurologic and psychological disorders, in the hopes of speeding up clinical trials and paving the way for personalized treatments.

“We know what our healthcare system is like, unfortunately,” says Shawn Paron, chief operating officer of the Alzheimer’s Society. “Especially for folks living with Alzheimer’s and dementia, or those looking to be diagnosed, it’s not a clear pathway. Having new innovations come to market that meet people where they’re at — that’s what’s crucial about investing in neurotech and biomarkers.”

“The benefits of noninvasive diagnostic tools are huge. They reduce costs, they improve access and they provide the potential for you to actually get treatment earlier on.”

Harnessing the power of data

Other startups leveraging real-life data to solve real-life problems:

- Perceiv AI is developing a platform that uses digital biomarkers to forecast disease progression in Alzheimer’s and other age-related disorders.

- Innodem Neurosciences is a digital biomarker and AI company that specializes in the development of eye-tracking tech for the neurological assessment of MS, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and cancer-related cognitive impairment.

- AiimSense’s proprietary brain imaging device combines electromagnetic tomography with AI to provide real-time diagnostic insight from traumatic brain injuries and strokes.

- Pragmaclin combines 3D cameras, remote monitoring and comprehensive reporting to help healthcare providers better assess people with Parkinson’s.

Katherine Ward spoke to Minna Woo, director of the Banting and Best Diabetes Centre and Gillian Einstein, who runs the Einstein Lab of Cognitive Neuroscience about the risk of ignoring gender differences in research.

3. Women’s health: Closing the gap in care

When it comes to health innovation, research remains dismayingly but unsurprisingly focused on men. As recently as 2021, for instance, scientists used exclusively male cells in originating cell lines in more than half the studies in which the sex of cell lines was documented. Another issue: because clinical trials require women to use contraceptives when they participate (to avoid harm to a fetus caused by an investigational product), we don’t fully understand how regular hormonal changes affect the ways medications are absorbed or metabolized.

But properly accounting for both men and women takes money.

“It takes resources to do proper trials and experiments, and to do them separately, literally means that it’s going to cost twice as much,” says Minna Woo, director of the Banting and Best Diabetes Centre at the University of Toronto. “This is why we need to invest.”

Such investment is coming, albeit slowly, driven in large part by female scientists, entrepreneurs and investors who recognize the deficiencies, distortions and dangers of this blinkered world view, as well as the enormous potential market for their solutions.

Market forces

Healthcare is one of the world’s largest and fastest growing industries, accounting for 10 percent of the GDP of most developed countries, and women dominate this market. They are responsible for a whopping 93 percent of over-the-counter pharmacy purchases worldwide according to one survey. Some projections suggest femtech alone could be worth at least $4.8 trillion globally by next year. Canada is leading in this space, and is considered to have the third-largest femtech ecosystem in the world. Between 2022 and 2024, $904 million in VC funding went to reproductive/fertility health, with a number of Canadian companies receiving notable deals.

There are growing opportunities in brain health, cardiovascular health and autoimmune disorders, and a number of local startups are focused on these and other conditions and diseases that specifically affect women.

- Afynia, a spin-out from McMaster, is commercializing the first diagnostic blood test for endometriosis, a painful condition that affects 200 million people worldwide, and whose proper diagnosis can take a notoriously long time.

- As an alternative to invasive, unpleasant tests for cervical cancer and STDs, Cellect Laboratories has created a nanomaterial that can passively collect cells from menstrual products for easy, fast diagnostic purposes.

- Maman Biomedical is similarly taking the pain out of fertility treatments, which can require self-administering dozens of injections during a cycle. They’ve developed a therapeutic patch that can administer IVF medication painlessly.

- Flutter Care is building a clinically informed perinatal health platform, starting with a connected medical device to prevent stillbirth, supported by a global community of users and early revenue-generating services.

- SanoLiving offers an AI-powered digital health platform designed to support women through menopause and healthy aging, providing personalized, evidence-based recommendations and access to care.

Significant deals in women’s health

Late-stage VC deals grew significantly in this sector between 2022 and 2024 in Canada and the U.S.

- 109 late-stage deals, 105 early-stage deals, 107 seed deals

- $13.4 million average deal size (90-percent increase from 2023)

- $1,521 million total capital invested (42-percent increase from 2023) in 2024

- Total number of deals fell in 2024 (183 deals in 2024 versus 221 deals in 2023), with fewer companies receiving larger-sized cheques.

Source: MaRS analysis of Pitchbook

Notable Canadian deals

4. Metabolic disorders: Fine-tuning treatment

GLP-1 drugs, such as Ozempic and Wegovy, have been the blockbuster, headline-grabbing darlings of pharma for several years now. With Novo Nordisk’s Canadian patent for semaglutide (the active ingredient in GLP-1 drugs) set to expire in January 2026, and generic alternatives soon available, their popularity will only grow. But, according to experts, treating Type-2 diabetes and obesity, the conditions they’re currently prescribed for, is just the beginning. The medicines work by mimicking a naturally occurring protein that lowers blood sugar. In short, they target metabolism, which is why they’ve been so good at helping with weight loss, but may also be effective in treating other metabolic-related disorders.

“GLP-1 medicines continue to surprise us scientifically, with a range of new mechanisms enabling exciting new opportunities for therapeutic application in the clinic, including arthritis, metabolic liver disease, heart disease and kidney disease,” says Dr. Daniel Drucker, a doctor at Mount Sinai Hospital and a professor at the University of Toronto, whose research collaborations led to the discovery and development of GLP drugs.

Currently, Drucker says, half of his lab is looking at how these drugs reduce inflammation and their potential use in treating Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Drucker adds that because of the remarkable success of these drugs so far, big pharma has re-entered the space after many decades of disinterest. “The great thing about our field,” he says, “is that we’ve had tremendous progress, which means the bar keeps going higher and higher and higher.”

Startups are also developing ways to optimize the delivery of these drugs. A new Toronto venture, Nymble Health, has created a digital patient support platform for users of GLP-1s that it describes as a “coordinated clinical team.” It’s neither app nor web portal but uses a simple user interface and AI to tailor behavioural guidelines related to diet, exercise and mental health, information about potential guidelines, and warnings about misinformation. “We still struggle with the delivery of basic care around obesity,” says Dr. Peneet Seth, the Toronto physician and founder of Nymble. The startup’s tool helps people who are on GLP-1 medications manage any potential side effects of the medication, and suggests other changes they could make such as modifying portion sizes and adding movement into their daily routines.

5. AI in action: The technology moves into practice

AI has the potential to disrupt the patient experience from how care is delivered to the workflow of providers and clinicians — in short, how the entire healthcare industry works. The economic case for this technology is still being worked out — especially at larger institutions. For broad adoption, successful innovators will need to find ways to translate their specialized technology into multiple use cases. Here are three key areas where AI is being most quickly adopted:

Helping lift administrative burden

AI is moving into more applications that can help practitioners in their day-to-day work. AI scribes, in particular, are becoming increasingly popular. Healwell’s December 2024 acquisition of Mutuo Health Solutions and its AutoScribe platform is just one indicator of this trend. Scribes offer an easily implemented solution to clinician burnout, arguably the biggest issue in healthcare, says Mahshid Yassaei, co-founder and CEO of Toronto startup Tali AI. “They spend 10 to 15 hours of their time each week, documenting and basically putting data into software,” Yassaei says. “Imagine some of the most intelligent and compassionate people in the country go to school for so long, to then be locked down behind their machine just doing so many mundane tasks.”

Tali’s AI assistant can do all those tasks: record and summarize doctor-patient conversations, facilitate medical searches and submit prescriptions requests. According to Yassaei, thousands of clinicians use the product every day, and, to date, it’s saved approximately 27 years of physician’s time. Relieving administrative burdens is also the goal of Phelix.AI, a platform that provides end-to-end automation of many routine healthcare tasks, including managing clinical documents, triaging fax requests, scheduling and patient intake. (Both TaliAI and Phelix received funding as part of the Health Compass II project.)

The note-taking space is becoming increasingly competitive, however, and the economic case is harder to make in large institutions. What will differentiate the winners in the coming years, industry watchers say, is an ability to extract insights from that documentation and apply these insights for patient care.

Linda Lifetech has developed a contactless breast cancer detection tool.

Improving care: AI solutions that bolster the patient experience

A number of startups are using AI to speed up access to screening services or to improve overall patient experience. Toronto-based Linda Lifetech, for instance, has developed a contactless, smartphone-based device that looks for heat patterns and blood flow that indicate cancerous tumours. Patients who show signs of possible cancer can then be moved to the front-of-line for mammograms, ultrasounds or further testing. At the enterprise level, a couple of startups have had great success in selling their AI solutions to hospitals and regional healthcare systems. FluidAI’s AI-powered platform uses the secure, de-identified data from Mayo Clinic Platform Connect to enhance its predictive algorithms in a project with Unity Health that’s designed to improve postoperative care.

Verto Health, meanwhile, specializes in applying AI to the unstructured data — encounter notes, discharge summaries and the like — that comprises 80 percent of all clinical information. They use that data (alongside structured data) to construct digital twins — real-time virtual representations — of hospital facilities or broader healthcare systems to optimize patient journeys and reduce administrative burdens. For the Fraser Health Authority, which consists of 12 hospitals, Verto has built virtual replicas of two million patients. The first phase, launched in February, allows patients to search for services and book appointments through a virtual assistant called Fraser.

Others are developing cutting-edge at-home diagnostic tools, like the aforementioned Afynia and Cellect. “We’re seeing a proliferation of those types of solutions,” Louise Pichette says. “One of the most exciting applications is preventative medicine, where you can diagnose something before you even have symptoms. It saves the healthcare system so much money because those people never have to get treatment.”

Drug discovery: AI solutions that accelerate the process

With the timelines for developing drugs and the costs of that development continuing to expand every year, there remains a lot of excitement around AI’s ability to make drug discovery faster, cheaper and more precise. Health AI platforms tied to drug discovery, in fact, are among the highest funded companies in North America (see sidebar). But only a few companies, such Toronto’s Biossil, are challenging the status quo and fundamentally changing the way drugs are brought to market. Biossil has focused on diseases for which traditional drug discovery has been stymied by population variability.

“Most groups are focused on applying new methods to a traditional process,” says co-founder and CSO Alexander Mosa, “whereas we are trying to develop a new process for drug development.” The sector nevertheless still faces hurdles, and a fair bit of skepticism. In the U.S., both pharma partners and VCs are mitigating against the riskiness of AI-driven drug design from biotech. AI-driven drug discovery candidates and targets have perceived risks for poor pharmacokinetics, ADMET assessment, and safety and efficacy for successful clinical trials. In-house vertical integration is seen as the safer bet.

Market shifts in AI applications

There was a large representation of late-stage VC deals across all health AI applications funding in 2024:

- 648 later-stage deals versus 583 early-stage deals and 688 seed deals in 2023

- $18-million deal size (55-percent increase from 2023) and $4.6-million median deal size (315-percent increase from 2023)

- Health AI platforms tied to drug discovery were among the highest-funded companies in North America (~$8.3 billion between 2022 and 2024):

- Xaira Therapeutics: $1-billion Series A in 2024

- Treeline Biosciences: $422-million Series A in 2024 and $261-million Series A1 in 2022

- Formation Bio: $372-million Series D in 2024

- Important acquisitions took place among Canadian AI drug discovery companies:

- Good Chemistry: $75 million to SandboxAQ

- Valence Labs: $47.5 million in 2023 to Recursion Pharmaceuticals

- Cyclica: $40 million in 2023 to Recursion Pharmaceuticals

Making a commitment

If there’s one thing that all startups specialize in, it’s uncertainty. The scale of uncertainty the health tech sector now faces may be new, but it’s also familiar.

“Being a founder is just extremely difficult,” says investor and MaRS advisor Katie Hayes. “It’s a very special type of person who can persevere through a ton of rejections on the capital side, rejections on the customer side, failure on the product side.”

But the thing that most helps founders navigate this uncertainty, Hayes argues, is community. Physically locating yourself among people and companies that are facing the same challenges, sharing research, being inspired by their wins, learning from their mistakes. MaRS is one place where community is nurtured and facilitated, but Canada has many others: universities and colleges, tech hubs, accelerators. Toronto’s University Avenue alone, with its collection of dozens of world-class hospitals and research institutions, all within a stone’s throw of the University of Toronto campus, is perhaps the most obvious example of this. It’s an enormous engine of idea generation, IP creation and economic growth. But perhaps we can go even further.

“Canada, and Toronto in particular, has extraordinarily strong science institutions,” says Brad Wouters, UHN’s executive vice president, science and research. “What’s really missing is just the ambition for Canada to decide it wants to be a life sciences superpower, and to make the commitments and investment to do that.”

Thanks to a new influx of talent, an historic sense of solidarity and a stable political system, the opportunity to make just those commitments and investments is here now.

Jason McBride, writer

Kathryn Hayward, editor

Richard Li and Grace Suh, data and analytics

Louise Pichette, Director of Health Sciences, MaRS

Andrea Teolis, designer

MaRS helps founders build their companies and create global impact. Learn how you can join our community of innovators benefiting from the MaRS advantage.