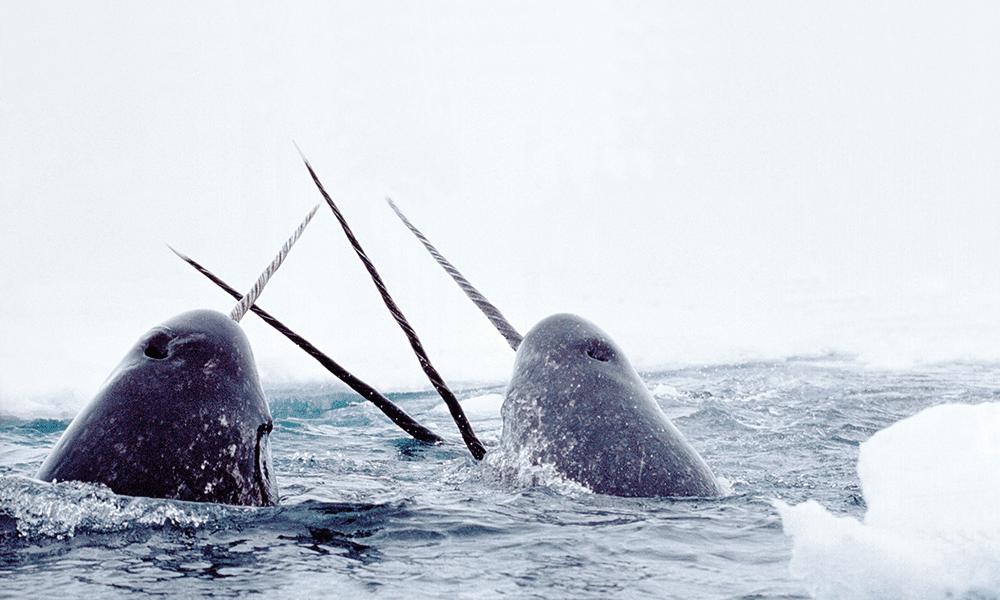

Canada’s narwhals are gaining on US unicorns

When the French pharmaceutical giant Ipsen announced in February that it would be spending US $1.04 billion to acquire Montreal biotech firm Clementia, the transaction showcase the remarkable narrative of a company that had sped from idea to acquisition in just seven years.

Entrepreneur Clarissa Desjardins founded Clementia after reading about an unexpected therapeutic application for a new compound: It wasn’t very effective against lung disease, the intended target, but did help people suffering from an exceedingly rare bone disorder. Seeing an opportunity, Desjardins, who has a PhD in neurology, built Clementia quickly with help from the Business Development Bank of Canada, which acquired a 14.5 per cent stake for $20 million (worth more than $130 million after the acquisition).

Clementia, observes Robert Simon, managing partner of BDC’s information technology venture fund, offers a case study in how rapidly scaling Canadian firms can surmount the billion-dollar valuation mark. It also shows, he adds, that Canada’s approach to tech innovation is producing results.

Such success stories depend on an ecosystem that not only encourages a proliferation of startups, Simon observes, but provides them with the resources and time they need to grow. He says that Canada is building an increasingly dense network of angel, early-stage and venture funds—“dozens where none existed 10 years ago.” They, along with traditional sources of capital, have begun to produce a species rarely seen thus far: “narwhals,” the Canuck term for what are known elsewhere as “unicorns.” These are tech companies estimated to be worth more than $1 billion based on investor valuations alone, that is even before they’ve been bought up or gone public.

Tech watchers say narwhals are crucial because, as “anchor firms,” they have the heft to attract talent, global investors and capital for further innovation. Several Canadian companies are closing in on this plateau, but entrepreneur and economist Charles Plant, a senior fellow at the University of Toronto’s Impact Centre, which tracks the phenomenon, says there should be more. The U.S., he pointed out in a recent study, has 150 unicorns, while the Kitchener-based Kik, the popular mobile messaging app, is currently Canada’s only example.

Plant does, however, see an upside: Within a year, Canada has almost doubled the number of firms on track to become narwhals. He estimates that last year 25 tech companies raised on average $40 million each (plus $100 million each for two healthcare companies) in new capital. More recently, a U.S. biotech company struck a deal in January with Toronto-based drug developer Triphase Accelerator that is expected to be worth $1 billion down the road.

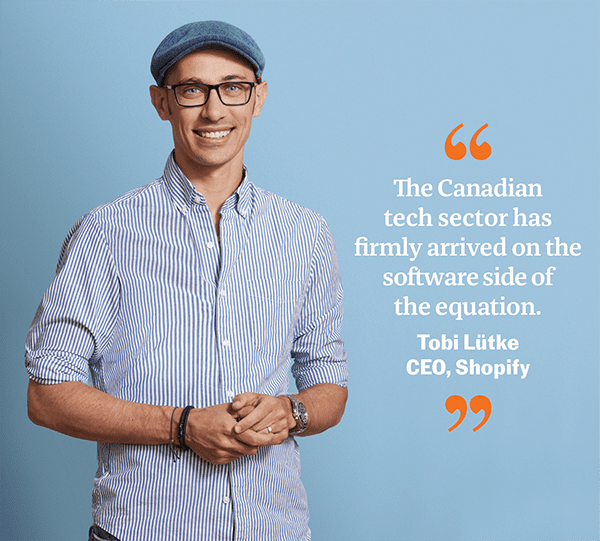

Canada also boasts a number of software giants that were once private-equity darlings, such as Shopify and Montreal-based payments firm Lightspeed, whose share offering in March pushed its valuation to $1.4 billion. Other rapidly growing Canadian tech firms include Slack, Hootsuite, FreshBooks and Element AI.

Their success, after the decline of hardware-oriented icons like Nortel, Research in Motion and JDS Uniphase, shows that the gears have been shifted. “The Canadian tech sector has firmly arrived on the software side of the equation,” says Shopify founder and CEO Tobias Lütke. Carol Leaman, CEO of Waterloo-based startup Axonify, agrees: The sector “is probably stronger than it’s ever been.”

There is certainly no shortage of startups, especially in southern Ontario. With thousands of attendees descending on Toronto for the Collision conference in late May, the global tech community will have a first-hand look at Canada’s densest innovation hub. The Toronto-Waterloo corridor is now home to 17,000 tech companies and 5,200 startups, as well as burgeoning fintech and artificial-intelligence sectors. Stuart Lombard, founder of the smart-thermostat developer ecobee, points out that tech firms benefit from the region’s diversity, cultural vitality and post-secondary research network.

Beyond southern Ontario, the biotech sector has deep roots in Montreal, which has also seen a boom in AI investment, while Vancouver is a centre of cleantech and game development.

The country’s open-door approach to newcomers has made it a destination for global talent. Simon points out that giants like Google and Amazon have been recruiting newcomers in their Canadian subsidiaries as a way of working around the U.S. immigration restrictions imposed by the Trump administration.

For all those pluses, Plant says his research has shown that Canada’s tech firms often stall in their growth trajectory because they have so much difficulty hiring seasoned sales and marketing executives. Leaman, whose Waterloo-based firm creates online micro-training modules for employers with far-flung workforces, says she has had to recruit in the U.S. because “there are not enough sales leaders who have that experience in Canada.”

Lütke, however, believes there are other factors as well. For example, some entrepreneurs simply sell their companies too early, for too little. Also, Canadian firms often seem more focused on discovery than commerce. “Canada really, really loves inventions and academic progress, but somehow doesn’t see the same value in the engineering-heavy process of getting a product to market,” says the Shopify leader and head of a federal advisory committee looking at a digital industries strategy. “I would love to turn that around.”

One obstacle in the way may be the relative dearth of larger tranches of investment money. Randy Cass, founder of Nest Wealth, a four-year-old Toronto designer of generic fintech platforms for financial institutions, says some companies have little choice but to go to the U.S. for serious financing. “I don’t think we have all our bases covered right now,” he says, adding that OMERS Ventures, operated by a large Ontario public-sector pension plan, is the only tech fund “writing $20- to $50-million cheques.”

Leaman, however, points out that some U.S. lenders are so quick to open their wallets that they may be creating a unicorn bubble. She has opted for a more measured approach and feels that massive cash infusions can not only cause ill-prepared startups “to get out over their skis” but virtually ensure that they are sold to buyers in the U.S. and eventually move there—a point of contention for many Canadian tech advocates.

Lombard isn’t so sure. While ecobee had to go south for scale-up capital, he’s confident the Toronto region, with its concentration of well-educated engineers and researchers, serves as a strong base as the company expands its suite of energy and home-focused products. And it doesn’t hurt that, even with recent cuts to U.S. corporate taxes, the cost of doing business in places like Seattle, San Francisco and Silicon Valley has skyrocketed.

“Those of us in Toronto’s tech scene know how strong it is,” says Nest’s Cass, noting how attractive the city is to young people. “There’s no other place in the world I’d rather be starting a company.”

John Lorinc

John Lorinc