How bots are making banking better

Challenged by nimble startups, Canada’s big banks are embracing AI, both to cut costs and compete. From chatbot service reps to predicting what will go viral online, the changes will be staggering.

The feeling of dread is nearly universal in our credit-addled society: Even as bills pile up and that retirement fund demands care and feeding, temptation rears its head — a pricey outfit, an impulse weekend in New York, that new iPhone.

Some of us are highly disciplined when it comes to managing our finances, but others avoid the math and end up overdrawn, if not deeply in the red.

ATB Financial, an Alberta credit union, recently launched a smart-phone-based personal banking assistant whose artificial intelligence (AI) technology effectively allows customers to outsource the management of their cash flow to an app.

Designed by Vancouver-based startup Finn.ai, the assistant automatically performs such tasks as creating budgets, tracking debt and sequencing payments by making predictions based on the customer’s spending and saving habits so they avoid bounced cheques or overdrafts.

According to Jake Tyler, chief executive officer at Finn.ai, banks may benefit because their sustainably solvent customers will have more savings since they can better gauge how much consumer debt they can handle.

Tyler believes they’ll also gain a greater sense of brand loyalty, pay less in interest and avoid over-draft fees.

“Every bank in Canada is looking at how to deploy part of what we’re talking about,” he says. “We’re going to see the market move quite quickly.”

Such partnerships illustrate how some fintech firms are increasingly inserting themselves into the space between financial institutions and their customers, many of whom now do much of their day-to-day banking on mobile phone apps with relatively limited functionality. Others are going a step further, grabbing ever-larger chunks of the consumer-lending business.

Without AI, banks could soon see their own “Kodak” moment

Eyeing these rapid changes, the giants of the banking industry are looking to AI for help. They hope these intelligent computing systems will allow them to automate certain customer-service and wealth-management functions, reduce their geographical footprint and develop more precise techniques for detecting fraud and money-laundering.

AI systems will transform the way banks interact with their customers both “in big and small ways,” says Ruby Walia, Head of Mobile and Online Banking for TD Bank.

Some observers predict that, for routine queries, online customer-service bots will replace personnel at branches and call centres within a decade. Others feel the shedding of jobs will happen even sooner. A survey of 600 international bankers by the consulting firm Accenture found that three-quarters believe bots will be ubiquitous within three years.

There are even those who argue that, if banking doesn’t find religion with AI, it may face what former Barclay’s chief executive Antony Jenkins recently described as its “Kodak moment” — turning the fallen photo giant’s famous slogan into a synonym for death by disruption.

Improving the customer experience

For example, Jordan Jacobs, co-founder and CEO of Toronto AI firm, Layer 6, says the lumbering sector has done much in recent years to meld pools of customer data gathered from savings accounts, mortgage and lending operations, and portfolio management.

“Banks have spent a fortune building these data lakes,” he says. “But they’re incapable of doing anything predictive with it.”

Layer 6 is marketing a set of algorithms that continuously scan customers’ interactions with banks for patterns to help predict how they will react. As Jacobs explains, if a customer has just had a negative experience — such as a conflict with a call-centre service rep over a credit-card transaction — the system can serve up measures meant to improve that customer’s next encounter, and thus seek to ensure the person doesn’t switch banks.

Yet, despite Jacobs’ skepticism, most Canadian banks are investing in AI capabilities, either directly or indirectly.

This year, former TD Bank CEO Ed Clark was instrumental in setting up the Vector Institute, a partnership between government, institutions like the University of Toronto, and the private sector to advance AI research, and drive its application, adoption and commercialization.

Located in the MaRS building, Vector’s public support comes from the Ontario government and the federal government’s Pan-Canadian AI Strategy. It involves five of Canada’s six large banks, plus several national insurers.

Fraud detection, cybersecurity, the stock market — all impacted by AI

As well as backing Vector, the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) has, like Google, set up its own university-style research lab with a mandate to publish papers and push boundaries, called Borealis AI.

TD, says Walia, has formed a licensing partnership with Kasisto, a machine-learning spinoff of the famed Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in Silicon Valley. Based in New York, Kasisto specializes in customer-service messaging platforms, and will help TD create a mobile chat application.

Scotiabank, meanwhile, has paired with another Toronto AI startup, DeepLearni.ng, on a machine learning application designed to improve debt-collection systems. The algorithm, says Michael Zerbs, Scotiabank’s Chief Technology Officer, searches for patterns that can help the bank contact account holders who have fallen behind in a way that prompts them to pay without getting angry.

As well, RBC has allied itself with high-profile AI researcher Matt Taylor from Washington State University, hiring him to lead their Edmonton lab, where he’ll conduct research and development in a range of fields, from reinforcement learning to autonomous agents.

The bank is also eyeing the stock market. Foteini Agrafioti, head of Borealis AI and chief science officer of RBC, says her group is analyzing historical news articles to predict whether tweets or other digitally transmitted messages will go viral on social-media networks. The purpose is to provide real-time analysis of incidents that may affect share prices of companies in the RBC investment banking stable. “We’re in a news-driven business,” she explains.

Agrafioti’s team of computer science and engineering PhDs is also conducting fundamental and applied academic research on various aspects of machine learning science, with an eye to developing applications in fraud detection and cybersecurity.

Robo-advisors will automatically adjust your portfolio

Banks are also edging cautiously into using AI for wealth management through low-fee robo-advisors.

So far, among bank-owned investment dealers, only BMO Nesbitt Burns has begun to offer such a service, known as SmartFolio. The field is dominated by independents such as Wealthsimple, a three-year-old Toronto “intelligent investment” startup backed by $100 million from Silicon Valley and Power Financial, a subsidiary of Quebec’s Power Corp.

These services, geared at younger investors not wealthy enough to qualify for premium investment advice, use machine-learning algorithms to shape and adjust portfolios according to changing market conditions.

“From a client perspective, it’s a potentially very valuable service,” says Prof. Eric Kirzner, a Wealthsimple advisor who teaches finance at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. But, he adds, “they’re not holding a client’s hand like a full-service broker.”

In other cases, AI contributes directly to the banking industry’s regulatory obligations. For example, algorithms can zero in much more effectively on unusual transaction patterns that point to credit-card fraud or money laundering. A recent report on advanced analytics by the Global Risk Institute concluded that the technology may be so accurate it will reduce the so-called “false positives” that currently soak up so much time and resources in financial institutions’ fraud-detection units.

Jacobs of Layer 6 notes that, eventually, machine learning will affect everything from generic internal applications — such as hiring — to the huge volumes of work involved in investment banking. One example: algorithms capable of evaluating large numbers of commercial contracts as part of the due diligence process required in mergers and acquisitions and corporate underwritings. Traditionally, Jacobs observes, such work is done by teams of lawyers and auditors, and can be extremely time-consuming, as well as costly.

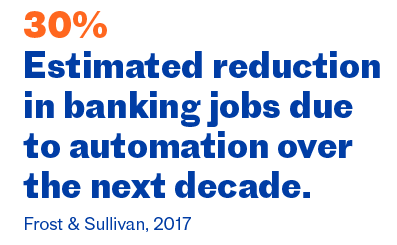

Implicit in all this, of course, is the prospect of huge job cuts. Antony Jenkins has jumped to fintech since leaving Barclays, and says he anticipates a 50-per-cent drop in banking employment in coming years.

Robots taking over? Not yet

Such predictions have drawn the attention of policy-makers at the highest levels, including Carolyn Wilkins, Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada. In a speech last April, she warned that AI “has raised the spectre of technological unemployment — the dystopian vision of an economy in which machines make many workers obsolete.” She also cited studies suggesting job cuts nearly as high as those forecast by Jenkins. When accountants and investment bankers are included, Wilkins said, technology could eliminate up to 40 per cent of “tasks performed by humans.”

But from his perch, Scotiabank’s Michael Zerbs says there is a substantial implementation gap between the entrepreneurial visions of startups and the institutional realities of large and complex organizations, where full deployment of advanced tech is “still many years away.”

Nothing can happen, he adds, until banks figure out how to deliver reams of machine-readable data suitable for AI algorithms. And still more turns on the ability of these organizations to put the much-hyped technologies into operation. The AI systems are obviously important, Zerbs says, but they’ll produce dividends only if banks prepare and execute effectively — an organizational transformation that, he adds, may take some time.

And, as the ocean liners of banking slowly change course, consumers may find themselves increasingly reaching for AI-based fintech services as they seek to manage their finances on their own.

John Lorinc

John Lorinc